The easiest, smartest way to imitate elite runners

When you're most tempted to abandon your best rhythm, authoritatively preserve it

I was talking recently to a U.S. coach who, while fairly well known to the running public and deeply respected by his peers, strikes me as underappreciated despite whatever renown he has amassed over his career. Every time I have a conversation with him about training, he reveals, without any conscious effort, how much more integrated thinking he has done than I have about most of the standard workouts familiar to anyone who has ever raced seriously on the track or the roads. (This may also be interpreted instead as an affirmation of my own rank ignorance of the essentials of the sport; regardless, this man is someone worth listening to, despite being unaware that he is never merely talking and always saying something.)

In this particular gabfest, we wound up on the topic of cadence, also called turnover or stride rate. I think we were having some fun with the elusive “most important factor” determining success in this ostensibly simple sport. While there may be no such single determinant, an undeniable commonality between elite runners is their high and essentially unwavering turnover throughout an event, even when extreme fatigue (within obvious limits) has set in.

Most observers agree that an ideal cadence for most runners aspiring to or at a certain level is close to 180 steps per minute, ideally split equally between the left and right feet. (I’m amazed that in all of the articles I’ve seen devoted to this vital topic, I’ve never once seen that last point emphasized. Try mixing it up a little and see what happens to your form.) Most slower runners settle into race-pace cadences of 150 to 160 steps per minute; this doesn’t drop much when they run less challenging paces, again perhaps hearkening to the “one true trait” of elite distance runners: They can shuffle with the best of ‘em during rehearsal, but when it comes time for the show, out comes the metronome.

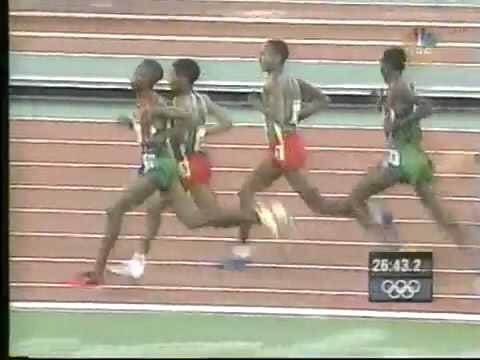

During our chat, my interlocutor mentioned the 2000 Olympic men’s 10,000-meter final in Sydney, anticipated as a showdown between the world record holder, Ethiopia’s Haile Gebrselassie, and Kenya’s Paul Tergat, the man whose mark Geb had snatched and the half-marathon world-record holder. Recalling how stirring the race was compelled me to ring it up on YouTube.

Tergat is close to six feet tall, Geb a good seven inches shorter. But watch what happens when Tergat decides mid-backstretch on the final lap that it’s time to knock the starch out of Geb’s withering kick. The two men wind it up immediately into a quintessential stride-for-stride contest. Not only did this in real time cause ten thousand and one running dweebs to leap to their feet in excitement in living rooms around the globe, the resulting video is wonderfully instructive, especially the replay starting at 3:37. (You’ll have to click on the “Watch on YouTube” link, because the IOC is an assortment of old, sagging, feces-encrusted scrotums. I could have just placed a link instead of embedding a nonfunctional video, but I choose to seize control where I can.)

Bronze medalist Assefa Mezgebu of Ethiopia appears to rally in desperation with a burst of slightly increased turnover in the final 20 meters in holding off Kenya’s Patrick Ivuti, but either way, this is an especially fulfilling example of a truism that trumps all of the other absolutes in distance running: If you can’t clip along for the entire race (until it’s time to sprint, if applicable) at something like 180 steps per minute, you will never be close to world class or even a successful collegiate runner, even if you have the VO2 max of an Alaskan Husky and spectacular running economy.

If you watch capable but non-elite runners start to fade, be it in a mile or a marathon, what almost always visibly fails first is cadence, rather than stride length [this originally read “stride rate” — sorry!]. (As a refresher, average cadence times average stride length over a selected time interval gives distance covered over that interval.) Obviously, a reduced cadence will soon drive stride rate down, but if you try to keep your cadence close to its ideal value, won’t this shorten stride rate anyway if you’re sufficiently tired?

Of concern to me is that, while coaches and athletes typically home in on turnover either during fast running or during sustained slow running (e.g., everyday easy runs on open, level surfaces), few to none I have encountered stress the importance of keeping stride rate during the recovery jog of a repetition session consistent and as close to fast-pace cadence as possible. In fact, almost no one I know even tries; it’s a miracle if you can get a small group of people used to a recovery of fixed distance and duration (e.g., 200 meters in 1:30, or ~12:00 per mile), let alone tell them how exactly what to do with their feet during the jog.

But if the idea of a speed workout is to replicate one or more aspects of a racing scenario, there is no role at all for the all-too-standard head-down, sloppy shuffle in the general direction of the next rep, something most runners habitually display even when they are only a rep or two deep into the session and still fresh. They may have learned this from Rocky movies, mostly the original one, and they need to forget it. Why not recover properly and keep clipping along at ~180 steps per minute?

I became convinced of the importance of this in roughly April of 2001, when I was in good enough shape to run a 2:24 marathon and doing some sharpening workouts with that spring’s eventual New Hampshire D-2 state 3,200-meter champion. This kid was truly a joy to train with, and also 6’ 3” and about 115 pounds of pasty-white rebar on the track. I could hear him over my shoulder matching strides with me on every rep as his dad would bellow at both of us to get Nate’s butt in gear—according to sources, I’m about 5’ 10.5”—and then every time we’d finish, he would somehow keep jogging and fall down at the same time, dragging and snaking his various appendages around the turn and breathing raggedly though all of them. Mostly to emphasize the difference— and also because knew I only had about six months left before this kid would be able to commence creaming me at any distance—I, no bastion of grace out there myself, would skitter along at the same cadence as the rep, telling Nate to give that a try.

But until that moment, I hadn’t really considered how beneficial sticking to a constant cadence from the start of an interval session until the final rep could really be from not only a psychological standpoint—it really does help to stay in a useful rhythm no matter what you’re doing and the range of physical sensations you’re confronting—but also owing to neuromuscular reinforcement: If you practice moving voluntary muscles in a systematic and repetitive way, the pathways involved—brain neurons, motor neurons and the motor units, or specific muscle-cell clusters, activated by motor neurons—become more adept at that specific task. As this process divorced from both aerobic and power considerations, you don’t have to run “hard” to achieve it. You just have to practice a lot.

I’ve never been a supporter of standing around between reps even when the recovery time is fixed; moving your leg muscles and joints, if not your legs themselves, at race pace when those legs are becoming increasingly tired has to have more value than standing in place, ceteris paribus. As someone who focused in his pale-green-salad days on the longer road distances, I believed, and still believe, that maintaining this habit gave me an advantage I would otherwise have been missing in the final miles of my better (and uglier, for that matter) races.

This advice, as you may have guessed, is contained within a broader dictum: Basically, run your optimal race-pace cadence whenever you find yourself running; otherwise, you’re both missing out on a chance to reinforce beneficial patterns and engaging in the reinforcing of less-optimal patterns. So when you’re just out for an easy run, resist—#resist!—the idea to lope and bop along like a happy puppy even though such lazy lollygagging can feel strangely empowering. At least I think so. At times, I’d just rather slither along like an amoeba than frantically whipsaw myself along like a spermatozoon.

Eternally with no plans to race in the next several days, I have no special reason to worry about my speed or form deteriorating further than it already has, and 85 to 88 percent of my running is done with a leashed dog anyway. But because I have an unwavering goal of mastering a short but difficult piece of music despite being an untrained hack on the keys, and that song happens to have a native tempo of 180 beats per minute, thinking about it while I run nudges me toward that golden cadence even if Rosie is alongside.

This is at 180 BPM, but in triplets—9 keystrikes per second, many of them correct.

Because not every conscious decision I make is part of a sadomasochistic drive to sob and guffaw my way into a nervous hospital, I rarely run with a GPS watch. But this afternoon I did, at least for a while (Rosie was along too), and this was the result.

I’m pretty sure that this run segment was unexceptional in every way. I also don’t know what good it does to post the data from one of my own runs, other than to vaguely suggest that despite never running fast for more than a few inches at a time nowadays, I have retained some of the habits developed and ingrained during the years I was competent and determined, if not especially fast, on the roads. One of them is to keep trying to resemble a runner.

So, if you want to pick one easy way to possibly get faster, be it directly through occult electrochemical-synaptic forces or indirectly as a result of accruing Emil Zatopek-caliber discipline and mental reinforcement, start with not farting around on rests between fast reps, and progress the following Tuesday to mentally playing a song on easy runs with a cadence of 90 (very common!) or 180 (not so much!) beats per minute and running to the silent beat. (Alternatively, you can listen to music and run at the same time. But small children read this blog, often as punishment, and I don’t want to reinforce any bad safety habits.)