Why the era of unedited, unresearched, unoriginal, unhelpful running content isn't for everyone

We can't be many weeks from "Why even wanting to work hard is exclusive to the genetically gifted"

In a post earlier this week, I demonstrated how perpetual alternative-fact-machine Emilia Benton, while arguing in Runner’s World that higher-mileage marathon training might lead to poorer marathon-race results, inadvertently made the very case she set out to disprove. An article two weeks ago for Women’s Running by Ashley Mateo, “Why the Era of Running Mega High Mileage Isn’t for Everyone,” provides a nice complement to Benton’s self-immolating December 2020 jabberfest by doing essentially the same thing—i.e., establishing that high mileage is in fact efficacious—but without any attempt at logical persuasion and with even more emphasis on a binary, “There’s us normies and there’s them elites” meta-physiology theme.

Before getting to that, I should add a dash of recently published background, which naysayers might frame as cynically poisoning the analytical well. Outside Run—like Women’s Running one of the dozens of quasi-journalistic brands perpetrated by Outside—recently published a list of its best 2023 articles, sixteen pieces chosen by its own editors. Two of these, the second and third on the list, appear to be offering frankly conflicting advice.

Apart from wondering how many alternatives were discarded before someone settled on “This year has been an exceptional time for running” as a catchy first sentence, I have to clarify that claim about “elite athlete memoirs.” No current elite runners had any books published in 2023. Two retired elite runners, Kara Goucher and Lauren Fleshman, had what might be called “memoirs” released last year. The distinction matters, because neither woman would have unfurled either the same manuscript or the same public antics in recent years as an active athlete.

Moving back to Mateo’s December 20, 2023 article, even the title is bizarre. What work, exactly, do the words “the era of” perform? The implication is that anyone uncomfortable with merely being alive while others are benefiting from high-mileage marathon training either needs to find a reliable time machine or jump off a bridge.

Below are quotes from this “anti-high-mileage” article, with some words given oomphasis by me. These quotes are obviously cherry-picked, but it’s easy enough to determine whether they fairly represent the overall tenor of the source article.

“Part of the high mileage appeal is that it truly does work,” says Kim Nedeau, USATF Mountain Running World Champion, running coach, and injury prevention specialist.

In marathon runners, a low training volume (less than 25 miles per week) was related to a slower finish time, and a high training volume (greater than 40 miles per week) to a faster finish time.

Nedeau generally recommends 20 to 40 miles per week (that number might increase a bit if you’re training for a longer race, like a marathon).

So, this article recommends capping your mileage right at the level it also argues represents the starting mileage point for runners who can reasonably expect significant improvements. If anyone might be expected to foment such a transparently flaccid idea, it’s someone who markets herself as an “injury-prevention specialist.”

Some of the stuff in the article is just weird. Like this, which Introduces the concept of the wild yet mundane statistical outlier:

Those numbers—and the results they yield—are staggering. They’re not totally outside the norm

And this:

A 10-minute mile consists of approximately 1,700 steps, according to research

Is there any good reason to not just say that the average non-elite runner takes about 170 steps a minute?

Much of the piece is devoted to convincing readers that the problem isn’t that high-mileage training is ineffective, it’s that this kind of training is risky to a recreational-jogging career:

For most runners, less may actually be more, in that accumulating less volume keeps you healthy and in the sport for longer.

Yeah, yeah. The lower the mountain you aim to summit, the less painful the tumble to the bottom if you fail. And you don’t risk burning out if you never come close to catching on fire in the first place. Et cetera.

If you’re satisfied with being a jogger, then by all means jog. But none of this refutes, or relates in any way to, the basic tenets of exercise physiology.

People who accumulate tons of volume can usually do so because they have years of training under their belt

This is the most cynical framing of “Be patient, and over time you can increase your mileage” I’ve ever seen. It implies that people should avoid “years of training” because this might place them at risk of progressing to, and benefiting from, “tons of volume”—perhaps as the result of heretofore occult genetic provenance:

“But there’s this delicate balance—based largely on genetics—that differentiates someone who could handle a ton or miles and someone who can not,” says Johnson. Elite athletes are genetically gifted…

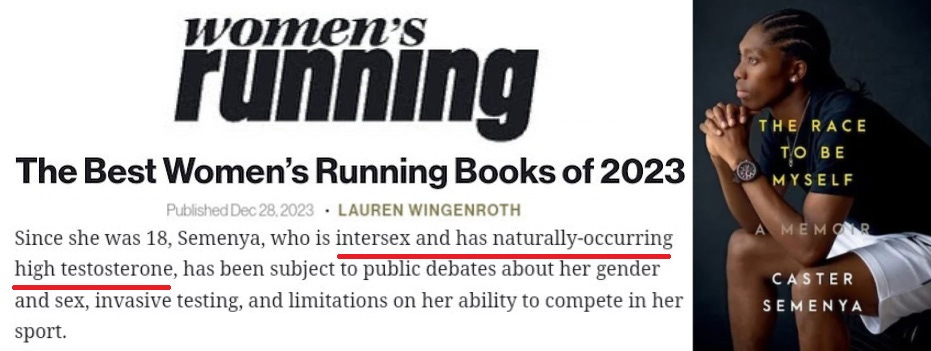

Women’s Running is very choosy when it comes to deciding whether human genetics is an applicable scientific discipline.

Caster Semenya has naturally occurring testosterone for the same reason I do: “She” has testes. This repetitive Wokish claim about “intersex” (male) persons is inane for the same reason as saying that any living person has a naturally occurring head.

Mateo also reveals the sadly parochial nature of her perspective on high mileage and everything else, which like that of everyone raised in the era of full-blown social media vastly overvalues form in relation to function:

Social media underlines the trend, giving runners unprecedented access to the training plans of not just elite athletes but other high mileage runners, which makes it easy to get seduced by the “more is more” messaging … In a culture where extremes are often lauded, it shouldn’t be surprising that many people would admire someone who runs 80 miles a week over someone who runs 40 miles a week.

Might it be possible that some people who patrol the Web for information are not coveting the training these ambitious runners throw down per se and are instead interested primarily in the results this ambitious training produces?

In case readers are able to remain immune while reading this piece to its real message—“Sure, high mileage works, but why should you bother with it?”—the final paragraph dissolves all doubt:

“There is a tremendous amount of time that goes into 60 or 70 miles per week compared with 30 miles per week,” says Nedeau. “When we think about the reward-risk benefit, the lower end might be a compromise, but it’s a pretty small performance compromise, and instead, you gain longevity, reduced injury risk, and the time to do all the things that busy amateurs do.”

“All the things busy amateurs do” today includes a solid couple of hours of Internet or steaming-video playtime that the average reader of Women’s Running, or even someone with a real full-time job, could easily surrender to gain enough time to run an additional five miles a day. And any coach who tells you the gains of moving from 30 to 60 or 70 miles a week are marginal at best is just a charlatan or a basic hack.

(Note: “are marginal at best” was added to the final self-owning sentence minutes after this post was published.)