2,000 days

Avoiding alcohol comes with no guarantees of personal or external sanity, but drinking is still about the ugliest way there is to kill yourself

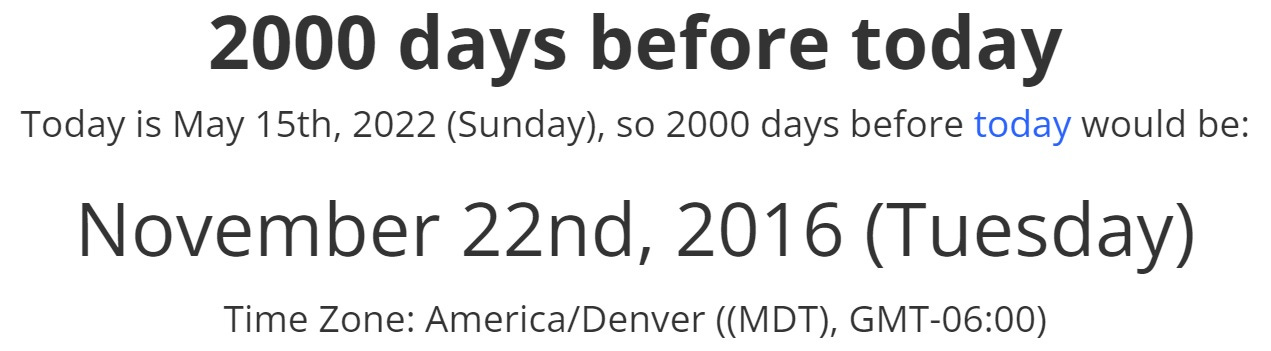

According to Google, now in the business of ranking search results in order of not so much their broad relevance as their popularity within the government, yesterday was my 2,000th consecutive day without potable alcohol.

November 22 was already a significant day in American history, but it didn’t cement itself a meaningful day for me personally until some months into the following year. This is because I had already quit drinking on dozens of occasions over the preceding twenty years, making it to at least 90 days ethanol-free at least a half-dozen times in just the previous three or four years. Rather than establish that stopping for good was in fact an option, the primary effect of this string of dry interludes was to suggest that I was in a permanent pattern of cleaning myself up for just long enough to stockpile resources for another miserable crash in some hotel room somewhere in the I-25 corridor, or, if it was warm enough, wherever the hell I wound up.

Increasingly often, I wound up in jail. By the end, it was always for the same thing: Getting a ticket for public intoxication or an open container, not remembering the incident and hence forgetting to show up in court a few weeks later to pay the $100 fine, and being found wandering the streets at some point after that, this time with a bench warrant associated with my name for a failure to appear in court. This always meant two or three days in lock-up, and it happened probably a half-dozen times between 2010 and 2016. By the end, I had become as familiar to certain police officers and local judges as any of the other chronic social washouts they deal with daily.

During the last of these excursions to the pokey, on November 8, 2016, I watched a presidential election on a jailhouse television. When the results were in, the consensus among my fellow inmates, although it appeared narrow, was that it was good that America would finally get a law-and-order president.

After I got out, I wasn’t done drinking. On November 22, I ran into Richie Martinez and his girlfriend somewhere on Baseline Road in Boulder, not far from where I have now lived for almost five years. When we met up, we were all sober, or close. I saw Richie a few more times after that before he died, but never when he was sober. We wound up getting a bottle and toting its contents around after distributing them among several one-liter bottles of green soda: Mountain Vodka. It was snowing out, and this ended as it was bound to, with me slipping in a puddle, cutting my head, and winding up at the local detox for yet another time.

This time, the next day, when my head was mostly clear, I decided to follow the advice of a friend with a unique function within the justice system, and take an extended vacation from killing myself just to see if that might have a salutary effect on myself and society. This took the form of spending a few months in what is best characterized as a state-funded, mass-sober-living environment in the middle of nowhere.

I had about twelve bucks when I arrived and had to borrow money from a friend that month to pay my cell-phone bill. This was not a new scenario. But I had a laptop and Web access, and by working for a few of the same online content mills that had been paying what bills I had during prior sober stints, I was able to quickly save enough money to return to Boulder and get a place of my own. I stayed a couple more months at “the fort” anyway, because I had the sense that there was more value in being clean for six months than the tokens available at A.A. meetings to commemorate such feats. I already knew I could stop drinking “for a while”; so did everyone else in my life. There was no assurance that my new experience would yield different results.

Yet for some reason, once I was back in Boulder, something was locked in place in my mind despite the ongoing determination of that mind to ruin whatever stability its owner managed to attain. The idea of falling into the same black abyss of despair had lost all its appeal. I knew I couldn’t escape my own miseries even in the inkiest blackouts, and was finally prepared to accept whatever mundane or even serious life setbacks I experienced in their raw, undiluted form.

I don’t do anything these days for formal sobriety maintenance. I stopped going to therapy in mid-2019, and when COVID-19 struck late the next winter, the few A.A. meetings I was regularly attending became Zoom-only affairs, which have no appeal to me. I’m in daily contact with people who know my history and inclinations, and being frank about the way I’m feeling probably helps maintain a barrier between my actual daily choices and the ones I made repeatedly for many years despite knowing where this would ultimately lead. Regular exercise obviously helps, as do a few other regular activities. And having a dog that relies on me not just for her basic care but for her moment-to-moment well-being makes a big difference, too. But mostly, it’s been a matter of accepting at the deepest level that any problem I believe I have at any time can only be made incalculably more painful by dousing it with booze. Often, there is no real optimism in this, only the bland knowledge that it would be easier for all involved if I just killed myself instead. And I have those thoughts, too, almost every day.

I don’t recall noting when I reached 1,000 days, which according to Google would have been August 19, 2019. But I was unquestionably far better off 1,000 days ago than I am now. I won’t list here the litany of specific contributing factors, many of which I have hinted at before. Instead, I can summarize the worst of their effects, which has been to leave me with no personal ambition and no desire to spend time in groups of people larger than two.

In fact, I have developed what feels like the inverse of an autoimmune reaction: Rather than becoming seriously ill as a result of my body’s grossly exaggerated response to a trivially damaging substance produced endogenously, I seem to be allergic to the presence of animated human flesh belonging to others. It’s not social anxiety, which would result in catastrophic nervousness and an unavoidable need to flee given situations. It’s more of a deliberative and persistent form of rank cynicism; I seem convinced at any time that someone in any group I find myself in is about to say or so something unnecessarily stupid, incorrect, or depressing. This could be me, but more likely it will be someone else. This has always been a basic fact of any social interaction, but now I have no tolerance for it. This has closed a few doors, probably for good, but at this stage of global confusion I’ll take staying in and running out the life clock over anything that might later be classifiable as a failed venture.

Will I make it to 3,000 days? That probably depends on how long my 8-year-old dog lives. I am far more confident in not taking a drink for the rest of my life than I am in that life spooling far into the future. Rosie gives me not only a serious responsibility but a great deal of real joy. When she’s gone, I’ll probably pull the rip cord. There is nothing I really want to do here on any sort of scale, and I’ve experienced more than enough experience. Just as I used to unconsciously structure my life so that I could and would eventually get drunk again, I now refuse to enter into any long-term professional or other commitments because I require the option of stepping aside with as little disruption to other people as possible. And this time, I know it.

None of this is news. I regularly saddle at least five or six friends with such niceties about my eventual disposition, which borders on cruelty but seems like something worth expressing. I’m almost amazed by how little value I place on my own existence and survival, and honestly, this time, it’s not me, it’s the rest of you lying fucking loons. I have always been a cynical person, but when I was getting drunk and fucking everything up, I at least wanted to rise to the level of those who were at least striving to treat others well and make something of their natural or earned talents. Now, other than a few close friends, I feel like there is really no one to impress or even pay attention to. The level of media- and government-issued bullshit in play ranges from irritating to paralyzing, and if this is the best people can now do, fuck it.

If I had kids or a partner or a solid career, which is as easy to imagine as me jumping clean over the Flatirons without a running start, I would probably be less affected by all of the ambient nonsense. But I’m glad I don’t, because, sober or not, I would be making those people miserable too. Isolation has its costs, but it seems like the best and really the only way for me to contain my misery while I do what I need to do to fund my and my dog’s life, and try to do those things well enough so that I don’t wake up in the morning on the defensive.