A longtime coach and a truly sweet man is gone, but impossible to forget

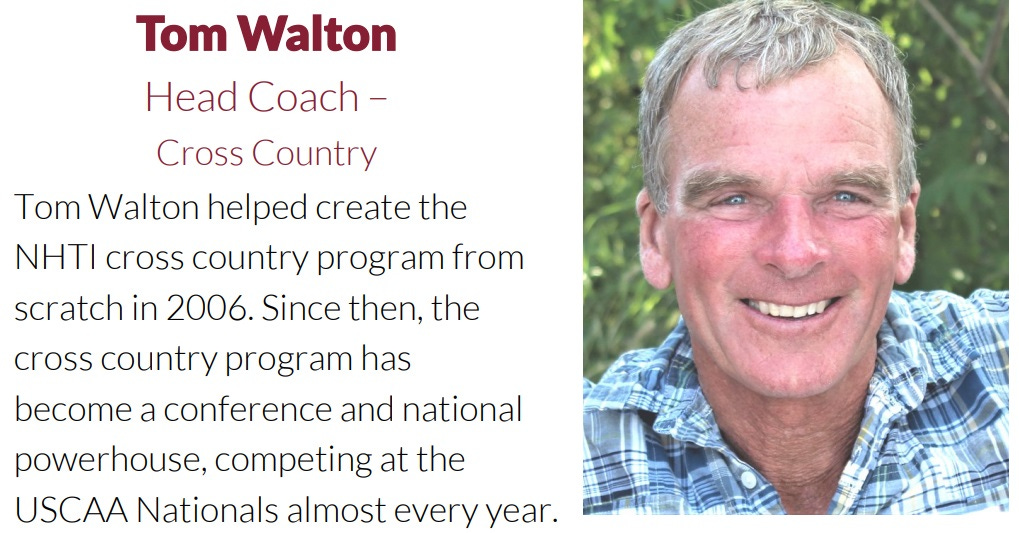

Tom Walton was the original ferocious yogi, with neither his competitiveness on the roads not his generosity as a person equipped with "off" switches

"Don't strive to be happy. Instead strive to make a positive difference in people's lives. If you manage to do that, you will be happy."

Tom Walton, a longtime Concord, New Hampshire-area distance runner, triathlete, and coach, died yesterday. This was ten days after he suffered a heart attack and was revived by family members who found him by the Contoocook River near his home in Hopkinton, and several days after he was removed from life support. He was 74, but he looked 54. On a bad day. As the article emphasizes, he was the least likely candidate imaginable, his age or almost any age, for suffering cardiac arrest.

I first met Tom around fifty years ago. My parents were friends with the Waltons when I was a toddler in the early 1970s, and I remember being at their home and playing with their daughter, who was my age. I even remember one of us toilet training, probably not me because it wasn’t my primitive crapper.

By the time I reached high school, Tom had become the Concord High hockey coach. But he was also already an all-purpose running promoter. I claimed here over two years ago that the Turtle Trot Five-Miler in April 1985 being my first-ever road race, but that’s not technically true. It was my first public road race.

The previous October, as a ninth-grader at Rundlett Junior High School wrapping up my first season of high-school cross-country at nearby Concord High, I had run the Blue Dukes Two-Miler, open only to Rundlett students and faculty. (The school mascot remains the Blue Dukes to this day, despite its simultaneous mockery of depression and glorification of monarchal systems.) Tom Walton was the organizer of the annual event.

Despite being of modest abilities (my best cross-country 5K time that fall was 19:38) I had no intention of losing the race to non-cross-country-team interlopers, teachers, or janitors, and established this immediately, being timed at 2:44 at the half-mile mark (from a pickup truck, so who knows) en route to an inelegantly victorious 12:38. That’s 5:28 per mile for the first quarter of the race and 6:36 pace for the rest of it. I soon stopped running this way whether I had a chance to win or not, largely on advice that afternoon from Tom. But were I to race again, I would make it an atavistic endeavor and proceed from the gun as if fitted with a Speedo lined with Ben-Gay. Which I might use as a kit.

Tom would not to my knowledge have run in a Speedo, but he would have been admired by women decades apart in age had he done so. He looked good for eons and couldn’t help but notice the looks and comments of others. And it didn’t help that the guy just never appeared to age, even for someone who took extremely good care of himself and appeared as stress-free as anyone can. I can’t recall when I last saw him, but even years ago the effect was almost unsettling; he was like Richard Alpert from Lost.

Ray Duckler’s Concord Monitor story correctly notes that Tom was a lamb of a person but a lion of a competitor. This is so common a tribute even in well-earned hagiographies that it’s easy to dismiss, but Tom really did walk this difficult tightrope. Most people who race hard and often and set high goals for themselves usually do a number on themselves along the way, not just physically but by slipping into patterns of overtraining, under-nourishing, and self-castigation. Anyone with such a mentality is well-positioned to be a coach or fitness guru, especially a guide of younger people.

When I was a high-school senior, my friend and classmate Ryan was on the hockey team coached by Tom. I remember the grumbling about yoga, but more importantly, I’m almost positive that during that year, if not necessarily during the hockey season, Ryan was dating Tom’s daughter, then a senior at Hopkinton High School and now a Denver-area resident. Maybe it’s just that everyone had a high-school buddy named Ryan who was always in oddly hilarious situations, but I’m fairly certain this happened.

Only now have I started to wonder what Tom thought at the time about this Brat Pack-movie scenario. He was a nice guy, but also a dad, a trait I’ve seen often prevail in such settings.

I am not sure what Tom’s won-loss record as a hockey and cross-country coach at various levels was, but it doesn’t matter. He was not the sort of coach who sought to build dynasties or collect trophies. Instead, he sought out kids who needed help the most, not just athletically but in their lives, and tried to convince them they were the trophies. He was on a constant hunt for underdogs and ways to help kids win, or at least get by, in ways that had nothing to do with them ever standing on podiums.

In the fall of 2000, in my second year of coaching cross-country at Bishop Brady High School in Concord, I decided the school needed to host a home meet for the first time in years. For this, we needed a cross-country course, which I created, or “created” (the land was already there). We also needed at least one team to come and race us, which wasn’t going to be easy to pull off because meet schedules tended to not change much from one season to the next in those days.

But even when offering only a few weeks’ notice, I was able to convince the first two coaches I thought of and contacted to bring their boys’ and girls’ teams: John Goegel of Belmont High School and Tom, then at Pittsfield High School. At the time, I maintained Web site for the Brady team, which, though no one under thirty is likely to believe it, was an uncommon thing at the time.

I happily “repaid” Tom a week later by attending a relay meet he’d organized in Pittsfield. You can see that over two decades ago, I already felt highly of him and his overall mission.

Pittsfield was a very poor town, and Tom told me stories of kids who went home after practice to dirt floors and homes without steady water or phone service. He believed that exercise and community could do things in the moment for kids like these that all the promises and social assistance in the world couldn’t touch.

In the right hands, this strategy works surprisingly well. Tom Walton, in addition to his admirable legs, had the right hands.

This story triggers fond memories as well as sadness, as these stories should. I worked with Ray Duckler at the Concord Monitor in 1997, when I was an editorial assistant who mostly handled obituaries and fought with grammatically challenged funeral-home directors over the phone and by fax machine. I also edited the Sunday church notes and somehow stayed out of trouble despite occasional monkeyplay.

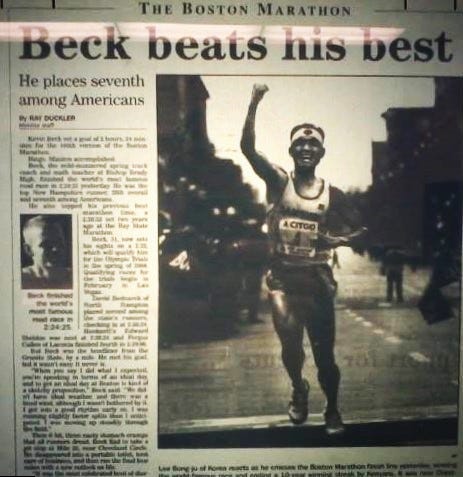

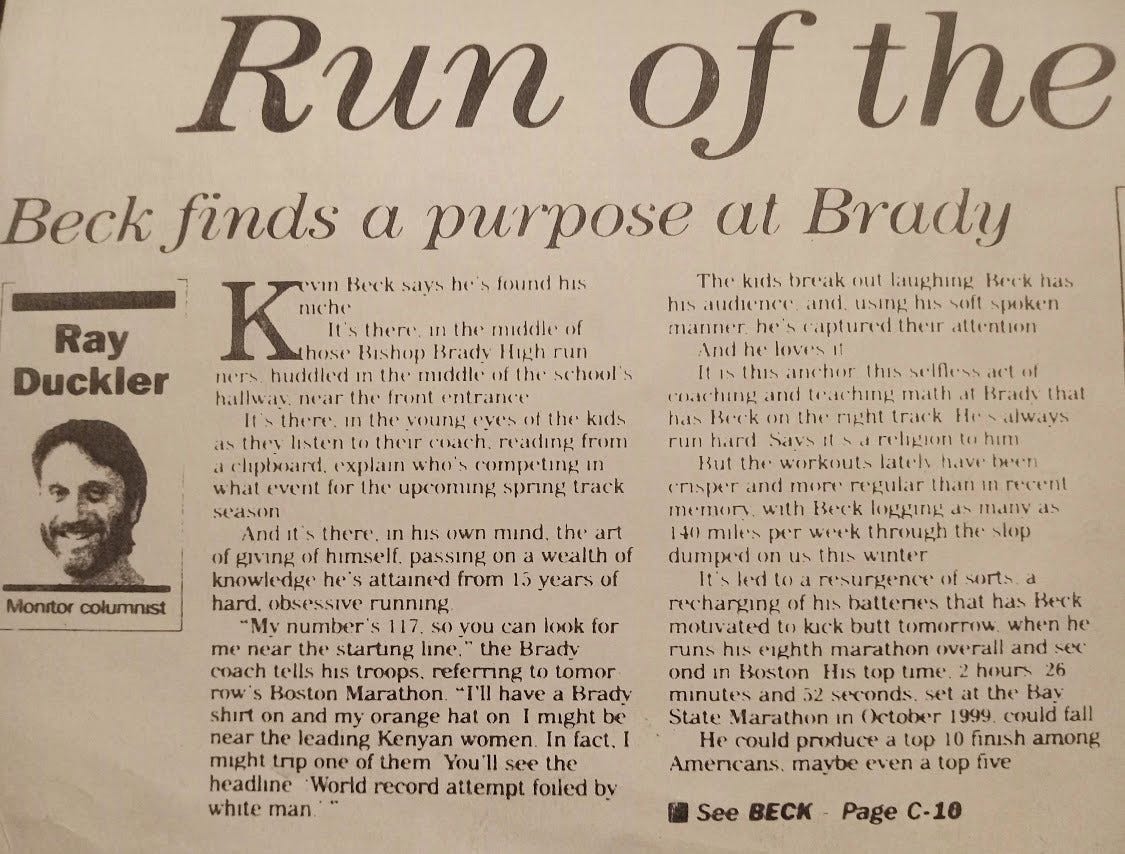

Duckler was then “just” a sports reporter. He’s probably still a Yankees fan. In 2001, he wrote pre- and post-race stories about my Boston Marathon effort that April, which proved to be a lifetime best (so far).

The words in these images are mostly unreadable for those unwilling to hurt themselves squinting, but I hear OCR technology is surprisingly good at extracting text even from photos of photocopies of newspaper articles gathered long ago from libraries via microfiche, for anyone who wants to try.

Duckler’s story also mentions Jim Graham. Jim became my friend in 1997, when he was also at the Concord Monitor as a reporter. It’s appropriate that Duckler sought comment from Jim, because Jim is very much in Tom’s mold. He watched me run some great races, in multiple instances lending moral support from a bike, and also saw me in some grim situations. He showed a rare combination of curiosity and empathy, which made him a great reporter.

He’s a low-key guy, but when a running or skiing event needs someone to help out, he has ways of showing up, unless he’s changed those ways in his comparative dotage. He’s been around Concord long enough to have had a significant positive impact of his own on the perambulating and snow-gliding scenes.

I could have filed this under “Personal Essays,” but Tom was a competitive runner, and though this is dwarfed by his contributions to the world as a human being, he was a significant part of my own growth as a nascent competitive runner as well as someone who over a decade later taught me lessons about what it really means for a coach to be dedicated to their runners.

And he never stopped competing, not in races, not on behalf of kids without much armor, not even when the ICU machines were stilled and his loved ones were ready for him to relinquish the battle. He’d done more than enough for a lifetime, but he was prepared to go on forever, chasing younger runners up and down Iron Works Road between meditative pauses and poses.