Foot Locker Finals: 1984 vs. 2023, punctuated by a sour and stentorian (but not quite room-clearing) belch

Force-fed foolishness has forced the average running pundit's intellectual curiosity and integrity to plummet dramatically, and the sport will never recover

The Foot Locker Finals, a race that brings together most if not all of the country’s best high-school cross-country runners every December, were held last Saturday in San Diego’s Balboa Park. Forty girls and forty girls took on a biblically arduous two-loop course that features a very tough climb but probably the most challenging descent of any widely used championship cross-country course in the United States.

RunnerSpace provided livestreaming of the girls’ and boys’ FLF races. That these were offered free of charge was sufficient to compensate for issues such as cameras on the lead golf cart failing just before the two-mile mark in both races, times shown on physical on-the-ground clocks not matching times displayed by RunnerSpace’s onscreen chronometer, and most of all the goofy, deafeningly uncorrected comments of race announcer and ever-genial airhead Carrie Tollefson.

After the 2021 FLF races, I noted that while the top performance lists for distance events on the track had been completely rewritten since the 1980s for both boys and girls, a startling number of the top all-time Balboa Park times were from that decade.

The lazy main hypothesis I offered for this finding was the lack of an analogue of track “superspikes” for cross-country runners. I’ve concocted a narrower as well as more accurate way to put this: Owing to basic topological factors, there is no conceivable way to create a shoe for the Balboa Park course offering the best kids of today what the best kids of Van Halen’s premier years couldn’t already do. The rare ability to tolerate both a long, steep, serpentine climb and the brutally abrupt descent that almost immediately follows—twice—is really the entire game.1

I also failed in that post to stress the obvious: Even if the Foot Locker Finals enjoyed perfect weather and course conditions every year, there are still precious few chances for fast kids to run at Balboa.

In any case, Melody Fairchild’s 1990 girls’ course record of 16:39 should have fallen by now, the annual dilution of the FLF field by events that did not exist 33 years ago notwithstanding. Maybe the most incredible thing about that run is that Fairchild, in an era without NXN or RunningLane events, was fifty-nine seconds ahead of everyone else. I still think this is the best cross-country race ever thrown down by a North American girl in the history of the sport.

Still, the record should have been erased already. I say this not from a basic “Come on, that record has now literally outlasted the widely understood lifetime of Jesus Christ, for Pete’s sake” standpoint rooted in speculative probabilities, but because in recent years I’ve watched a string of runners demonstrably fit enough to break the record arse up their chances with extravagantly piss-poor pacing.

The girls’ field this year included what had to be a half-dozen girls who had already broken 10:00 for 3,200 meters and a ninth-grader who ran 16:22 on the track in the spring as a middle-schooler. But Rachel Forsyth decided to compete as if having just robbed a bank in broad daylight without the benefit of a getaway car, ripping through the half-mile in an astonishing 2:23—that’s sub-14:55 pace, fast enough to usually win the boys’ FLF race—and coaxing a group of girls trying to hold back through an also-very-quick 2:33. This is borderline insane, and Forsyth’s brave but clearly Icarus-like gambit dictated that Fairchild’s record would in all likelihood stand for yet another year. The announcers made no mention of what Forsyth’s pace really meant—they only compared it to the half-mile splits of other girls who had been successful on the course.

Forsyth went through the mile in 5:00, at least according to one of the clocks I could see. She was still ten seconds ahead of the pack, but she had split that very fast mile in an ugly way (2:23/2:37) with the first of two trips up the hill ahead of her. Tollefson’s observation, or allegation, that Forsyth was in fact speeding up at this point would have seemed odd coming from almost any other veteran commentator.

While it still looked like Forsyth might win, any chance of her running under 16:40 was already all but gone. She would need to run 5:31 pace the rest of the way to do it—four half-mile segments over the hills in 2:45-2:46. And the girls who came through the mile in 5:10 had gotten there wisely (2:33/2:37), someone in that group would need to run about 5:26 pace the rest of the way to set a new record. This seemed more likely than Forsyth holding on, but still farfetched.

By the two-mile mark, it seemed that any shot at the record had evaporated. Elizabeth Leachman wound up coming reasonably close with a 16:50, but wound up winning by nearly fourteen seconds. Forsyth held on for third, averaging about 5:45 pace for the final 2.1 miles after her five-flat opener. Despite the greater difficulty of the latter stretch, Tollefson seemed to be reaching fairly far up her own ass when declaring in the aftermath that Forsyth had run “a great race.”

When the boys were on the starting line, Tollefson averred that viewers could expect to see some yet-unknown fellow or fellows pull the same thing Forsyth just had, perhaps because they had just seen exactly how well this strategy had worked. When instead the entire field was as close together as possible a quarter mile into the roving scrum, Tollefson remarked on this as if she herself had not predicted exactly the opposite minutes earlier.

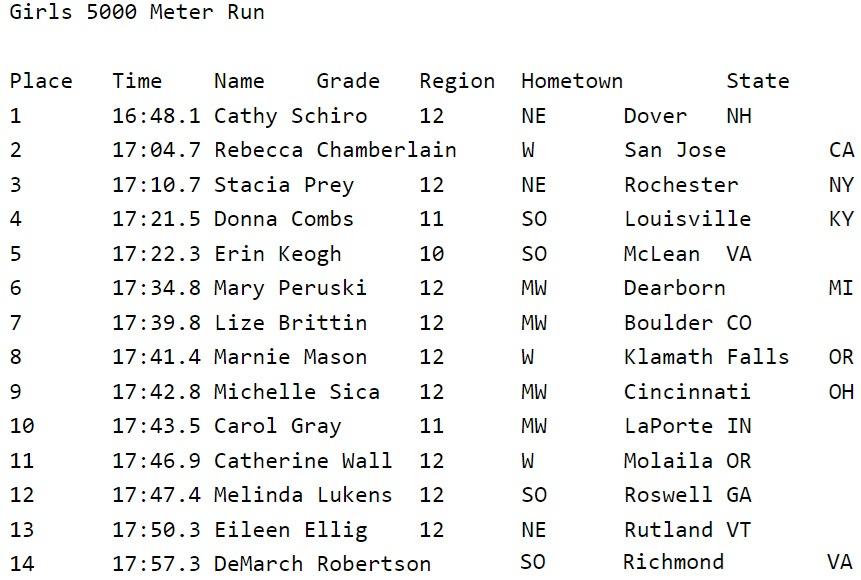

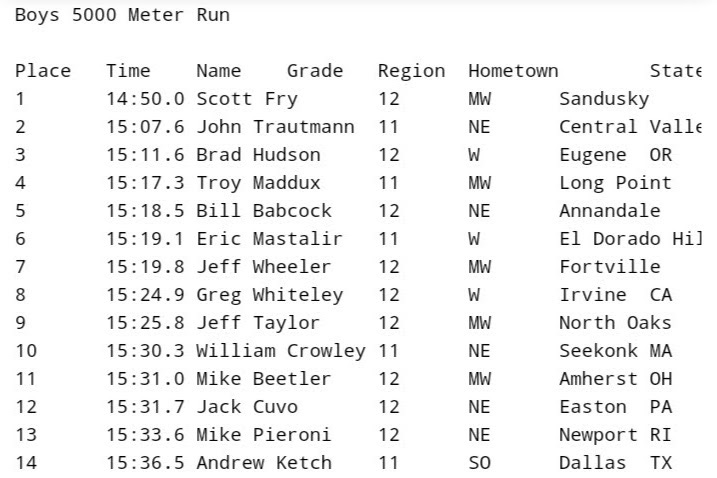

The results of the 2023 boys’ and girls’ races were very similar to the results of the 1984 races. Among many musty choices for comparison, I chose that year mainly because I know or have met a disproportionate number of people who participated in those races, and partly because the fall of 1984 was my introduction to cross country. I limited this comparison to the top fourteen finishers in each race because RunnerSpace was displaying the results in its livestream in sets of seven finishers.

Not quite a perfect match, but remarkably close. And I don’t think the expansion of the field from 32 runners in the Pleistocene Era to 40 today has had a significant effect on the top fifteen times in each race every year.

It would have been beautiful to see Cathy Schiro and Fairchild come along at the same time and race for the national title at Balboa. They had similar churning, compact styles that translated into deceptive adroitness at overland perambulation, although Schiro made her top gear look more effortless. Schiro had already run 2:34:24 for the marathon in May at age 16 at the first-ever U.S. Olympic Marathon Team Trials for women in Olympia, Washington, briefly surging into fourth place in the final two miles before settling for ninth.

Schiro (now Cathy O’Brien) went on to make the next two Summer Olympics in the marathon. She was beating the Too Much Too Soon pandemic before it became cool to do so and then for the world to finally acknowledge that the TMTS pandemic was almost entirely a contrivance all along, one fomented mostly in the mind of resentful washouts or runners who really had been pounded into the ground by ruthlessly idiotic coaches.

Other than 1984 champ Scott Fry’s 14:50, the results of the boys’ races from last weekend and from December 8, 1984 are also remarkably similar.

The 1984 14th-place girls’ and boys’ times sum to 33:33.8, while the 2023 14th-place finishers’ combined time was 33:34.1. The middle of the FLF field looks about the same as it did four decades ago. And 1984 wasn’t even an especially perky year for the era in terms of the times.

It would take a lot of work to convince me that Tollefson is a bad person. I interviewed her for Running Times in 2004 after she became the only American woman to qualify for the Summer Olympics that year in the 1,500 meters (the original Web version is here, and the version Runner’s World pimped for own use for a few years after buying Running Times is here.

Although Tollefson isn’t the sharpest card in the shed, she seems sufficiently on the ball and capable of research to reject the idea of doing a podcast with far-ranging fraud Latoya Snell and repost all of Snell’s fictitious accomplishments with the show notes. But in September, Tollefson did just that. Snell is not the only public degenerate Tollefson has collaborated with lately. And I would say “even Letsrun protects Snell,” but there is no “even Letsrun” anymore, if there ever even was—those retards have their own undisclosed agenda(s), and they keep establishing emphatically and in deeply hypocritical ways that they have sided with the auto-fellating snowflakes and psychotic skanks occupying outsized, stolen roles in media when they wouldn’t be fit for purpose in basic data-entry jobs.

Running has become so infected with imperious harridans, imbecilic overgrown rich kids, and industry-protected fakers that even a lot of decent people whose income is derived from weekly podcasts or other forms of alternative media have become contributors to the rot. I used to think people close to my age were more immune, but this often depends on how willing they are to divorce their income from their stated opinions.

Some podcasters, like David and Megan Roche, have been open scammers from the start, with the aim of attracting attention by imitating smart people in a way only their peers—shitlibs deluded about their own intellectual prowess—could possibly swallow. There are probably no two worse people in all of running, and certainly none with a more irritating, clueless, and boastful array of dopey and doping-happy clients. But other podcasters, especially former “name” runners like Tollefson, often start their careers with noble enough aims but eventually find themselves cycling conspicuously degraded but also conspicuously popular (or at least faddish) figures through whatever jabber-mills they operate. If this results in any twinges of conscience, they can easily rationalize these away on the basis of hiding in a particularly vulgar or sordid crowd; after all, what’s one more openly self-debased Gen X or older Millennial former big-name runner with a podcast among many? C'est la vie.

Snell and her chortling, illegitimate ilk deserve no role in the sport. But most of the people who keep them afloat with positive publicity for sham achievements are just too parochial-minded, gullible, and self-interested to vet their subjects or consider the greater impact of glorifying outright liars in a sport where it’s painfully easy to not cheat. Deliberation is a thing of the past; today is about sheer, often ill-considered or outright-ignored impact—hits, shares, and click-based revenue.

As a result, there’s no shortage of sheer digital chum out there and a lot of scavengers pleased to have a place to swim or at least thrash around in. And God forbid anyone ever call for even a half-assed clean-up job.

I say this while admitting that for decades, I didn’t foresee a way to make track racing shoes significantly or even any faster before being proven wrong by the arrival of Nike’s ZoomX insole technology and related innovations.