Outside publishes a drug ad by a medically atypical, disingenuous author disguised as a "running is no panacea" advisory

Be on the lookout for this "drugs are good, m'kay?" crap everywhere, especially at your doctor's office

The first book about distance running I ever read was called The Complete Book of Running. I received it as either a birthday present or a Christmas gift in late 1984, when the book was seven years old and I myself was turning a running-, Boston Celtics-, and masturbation-crazed fifteen.

The book’s author, Jim Fixx, a Time-Life editor who had quit smoking and discovered running at around the age of forty, had put a glorious exclamation point on his magnum opus that very July by dying of cardiac arrest while on a run in Hardwick, Vermont. The following month, after some of the inevitable jokes on programs such as The Tonight Show about the undisclosed “health benefits” of “jogging” had waned, my mother suggested I take up distance running myself. I like to think this suggestion was more because Joan Benoit, who lived only a few hours away, had just won a gold medal in the first-ever Olympic women’s marathon than because of the ultimate arc of Jim Fixx’s life. But she (or Santa Claus) did get me Fixx’s book after my maiden season of cross-country while knowing his fate, so…

The point is that sensible people have known for decades that running can only go so far in overcoming unfavorable genetics (i.e., bad luck) and adverse lifestyle choices (e.g., excessive alcohol, nicotine, or glory-hole consumption, or doing anything the U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends). This doesn’t mean that regularly emphasizing the message is valueless, as there are always people new to running and giddy about the “pink cloud”-stage changes to their bodies and minds who could stand to hear that they’re not invincible.

But over the years, as the pharmaceutical industry has gained more and more control over the editorial content of the publications in which they advertise their gunk, these “running isn’t the only thing you can do for your health” stories have become more heavily laden with “in the end, you’ll probably need medication no matter what” messages.

Outside, which publishes the gleefully superfluous and disorganized online rags Women’s Running, Trail Runner, and Outside Online, is currently a privately owned company, evidently still awaiting “a runway” toward an initial public offering. Since it’s not yet a publicly traded company and never should be, its head honcho, Robin Thurston, is not technically beholden to ensuring that his offerings demonstrate the slurry of demented ESG and related requirements companies must fulfill to remain in good standing with the globalist elites who determine all companies’ fates. But if Thurston or anyone else decided to take Outside or any firm like it public, it wouldn’t be worth a vegan-fart in a crowded elevator plummeting toward “nonbinary” hell unless its content were maximally enriched with pro-Wokish lunacies and pro-business messages.

This is why all of Outside’s editors and regular freelancers are doggedly clumsy producers of slapstick-level content about racial justice, the latest antics of neo-trannies, and profiles of assorted other flavors of cavorting and capering identity-grifters, with these pieces often grafted onto cloddish advertisements for the authors’ own equally science-based and well-vetted “coaching” services.

On October 20, a piece titled “No, Running Isn’t a Silver Bullet for Health” was published in both Trail Runner and Women’s Running. Its author dispensing what amounts to general medical advice after waiting until the very end of the piece to disclose that he has a rare congenital heart condition called patent foramen ovale (PFO) by itself dissolves any legitimacy the piece might have had. But even without this instance of quasi-deception, the article is rife with other idiocies; you just have to know what to look for.

The author, Alex Kurt, is 36 years old. He describes being surprised to learn this past summer that the state of the surface of his four-month-old red-blood cells indicates that he’s on a path toward being diagnosed with diabetes erelong. He shouldn’t have been surprised at this at all, and in fact probably wasn’t, since he had been walking around with alleged hyperlipidemia for fourteen years—a fact about himself Kurt saves for the middle of the piece:

at the age of 22, I was prescribed simvastatin–a medium-intensity drug that reduces the amount of cholesterol produced by my liver. It didn’t make for the sexiest bio line in the dating apps, nor did my upgrade at age 29 to atorvastatin–a high-intensity drug they give you when the lighter stuff still isn’t cutting it. (My numbers went down but were still too high.)

If you’re a standard consumer of the American medical system, you probably don’t see anything especially strange about this progression of prescriptions, other than the early age of onset. But in fact, it should jump out at everyone as badly misguided, because here’s the same story, differently worded:

I was put on a type of drug. Seven whole years later, it had done nothing, so I was put on another drug with the same mechanism of action. I never asked why I got the less effective one in the first place or why my cholesterol numbers didn’t meaningfully change throughout my twenties. I never asked how these numbers correlate to real-life outcomes, either. Good thing, because no one actually knows. Oh, and also I didn’t ask what made the replacement drug so much better.

“Statins” act on the body by limiting the activity of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, the enzyme responsible for the rate-limiting or “bottleneck” step of cholesterol biosynthesis in the human body. “Statin” is the suffix the generic name of all drugs of this type—see also “-pril” for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and -tidine” for H2-blockers—and is easier to say than “HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor.”

I’ve made several brief and unflattering references to statins on Beck of the Pack just this year. The most helpful was probably an images-only post in August that noted that in 2018, simvastatin (most often sold as Zocor in the U.S.) and atorvastatin (Lipitor), the same two drugs Kurt advertises having been on, were both among the top five most commonly prescribed medications in the United States.

Elsewhere in that post, you’ll see evidence from an analysis of eleven long-term studies examining all-cause mortality in long-term statin users that these drugs—which are not without significant side effects—add an average of roughly four days of life to people who chronically take them. But no one in the medical world gives a rip about that, because statins are and long have been enormously profitable chemicals. Statins were already earning their makers $19 billion a year two decades ago, and as of 2019, Lipitor alone was still raking in $2 billion a year for Pfizer despite its patent having expired eight years earlier.

My incomplete medical-school education included lessons that would prove valuable many years after I abandoned that project over halfway through. Some of these pertain to medical concepts themselves, but more critical that that is knowing how physicians who worked in outpatient settings used to operate and wanted to operate.

In the mid-1990s, most docs I shadowed, especially the older ones, preferred to not put people on new prescription medications unless there was nothing the doc could do in the office to ameliorate a newly detected or worsening problem and no strictly operational changes a person could make after departing. This is partly because they noticed that people on certain drugs tended to wind up on these drugs for life, probably something to avoid whenever possible. But it was also because reflexively handing out a drug for every problem was something a pharmacist had enough knowledge to do, or really anyone with access to a Physician’s Desk Reference (PDR).

These docs also detested pharmaceutical reps and especially the way these reps courted medical students with free pizza, fanny-packs, even pens. I’m pretty sure they knew that the capture of medical practice by drugmakers already then underway would progress to a point where doctors were little more than dope-dealers. I didn’t grok this at the time, even though a few of them were openly wary of developments like children being placed in large numbers on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), then a relatively new class of drug (and another class of medication we now know doesn’t work as advertised).

It bears noting that the science I was taught about saturated fats was a giant load of horseshit, founded on a couple of bad studies in the 1970s or before. The state of “cholesterol science” was also in flux—as it still is. Instead of just a “high cholesterol level” now there was “good” and “bad” cholesterol (not the terms I was taught). Since then, granular ideas about the role of the different lipoproteins incorporated into cholesterol molecules have shifted.

Not surprisingly, a given serum cholesterol level and lipoprotein profile can and usually does mean different things in different people. Most people don’t fast for their tests like they’re supposed to, bitching up their already scattershot results to varying degrees. Also, since our bodies make cholesterol, there’s only so bad the stuff can really be. True, our bodies also make urea, faeces, menses, boogers, and semen as well, but we feature specific openings for casting these substances into the external environment; moreover, there are steep physiological (and social) prices to be paid for their prolonged internal storage.

Doctors prescribe statins not because they help people but because they make a handful of powerful people a lot of money and don’t kill recipients at a noticeably higher rate than non-recipients.

While those open bribes from big-breasted, cleavage-flaunting drug reps are no longer legal, coercion and making news laws to make that coercion easier still is, and this pressure operates at the level of whole physician practices—that is, in practical terms, universally. In February, I wrote about how pharma has gained a greater and greater foothold in not only medical practice but medical education in the many years since I left the environment.

Since I am adept at avoiding going to doctors myself, I have been slow to appreciate how much everyday medicine has become dominated by the rip-roaring distribution of mostly pointless pills. One silver lining of the covid scams has been a fuller realization and admission on my part of how corrupt and outright dangerous “healthcare” has become.

When I describe the most popular prescription drugs as “mostly pointless,” I’m talking about the fact that ACE inhibitors, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, and calcium-channel blockers haven’t curbed hypertension or at least cardiac deaths, which are associated with chronic hypertension—a laughably easy condition to diagnose in someone without any cardiovascular problems or risk factors.

And that cancer rates are still on the rise despite the prevalence of anthracycline-class antineoplastic drugs like doxorubicin (Adriamycin) that have been around since the 1970s and have damaged far more hearts and other organs beyond repair than they have saved or prolonged lives despite these drugs being considered effective chemotherapeutics. (Very much apart from that, a sincere bow to anyone who toils in earnest in an oncology-related field.)

And that obesity and diabetes are both still increasing in prevalence despite metformin also being among the top five most commonly dispensed meds in the U.S.

And that both beta-2-receptor agonist inhalers for asthma (or “asthma” and thyroxine/T4 for hypothyroidism (or “hypothyroidism”) are distributed like water at a half-marathon.

The next time your doctor wants to put you on a new medication, ask what the real risks are of going without. Better still, if you’re on any of the typical chronic medications Americans now get as a de facto rite of passage into middle and old age, ask your doctor what the risk of going off them would be, especially if the relevant clinical data haven’t changed. Put it the way I did when I had no insurance but occasionally found myself confronted by doctors anyway: “Pretend I live in the middle of nowhere and simply have to make do without this drug no matter the physical consequences. How do I best enjoy life anyway?”

You may not get an honest answer, because so many doctors—including many who hate themselves for it—have to write a given number of prescriptions of else find themselves not working for the same practices anymore. You probably also won’t get an honest answer about covid-jabs side effects, either. Nothing against doctors themselves, but anyone who wants to remain healthy should avoid them like lepers. I understand that routine trips to healthcare professionals are unavoidable for many people, especially those with chronic conditions and who are getting long in the yellowing teeth. But the healthiest people I know never go to doctors and systematically shun nonessential prescription medications.

As cynical as this may be, it’s also an ineluctable consequence of the American healthcare system. Healthcare is not a service in the United States. It is a business product, and the people who run the largest companies couldn’t possibly care whether perfect strangers die as a direct result of decisions they make. People like Rick Scott look like cadaverous, leering monsters because in nature, form often suits function. Because profit is the only relevant metric, drugs that actually sure or effectively treat medical conditions are bad news because then the number of sick people goes down.

But what if millions of people—dupes like Alex Kent—could be kept on the same drugs for years, often by being told (and some docs actually believe this) that their not-improving blood-pressure or blood-glucose numbers would actually be worsening if they went off their meds? Ah, now there’s a prescription for nonstop shareholder bonanzas. And that is just how American medicine now works: Dose it and charge its insurer, but don’t improve its health or it won’t have to come back.

Kurt goes on to ask, “is there a point where the returns diminish or even backfire a bit?”—whatever half-awake mongoloid edited this piece asked the unrelated question “Is There Such a Thing as Too Much Exercise?” in the heading above the corresponding section—and observes that if you’re at risk for diabetes or heart disease, while dietary modifications can be effective in some people, you might need some meds, too.

But, as already noted, Kurt also waits until near the end of the piece to throw in the nontrivial fact that he has a congenital heart defect, meaning that he’s someone with unusual physiology and whose experience would be unwise to generalize.

Early in the piece, Kurt wrote:

The doctor’s main point was this: You can be young. You can be super fit. You can be outside of every “risk group” on paper—but your risk isn’t zero.

That’s great. But someone with a heart like his is not “outside of every 'risk group’ on paper.” And he knows it. (That said, I give the guy honest credit for not giving up in the face of a number of unusual challenges to the very systems he’s committed to using and strengthening.)

I strongly advise that, in addition to not taking anything Outside publishes seriously, everyone do their best to staying away from doctors or at least prescription medications. This isn’t because medical providers are malevolent or inherently incompetent. In all seriousness, ever since the covid debacle started, most of them have been too constrained by fear to be honest about the jabs and other “viral” issues, and a lot of doctors really aren’t very informed in areas they never explored after medical school, including the sound use and interpretation of statistical data.

Med students have also always been taught have a reflexive respect for authority, such as the American Medical Association, and for many doctors this tendency never goes away.

There is a purely practical element to my suggestion, or imprecation, that people wean themselves off non-critical medications. While none of us can prevent the pathological machinations of the medical-industrial complex framed as a “healthcare system,” if enough people simply refuse to use their products, they can’t make money. I know this is a fantasy, but it’s at least theoretically possible. Unlike giving up, say, food, which now costs roughly twice as much as it did five years ago thanks to the freewheeling recklessness of those in charge of America’s purse-strings.

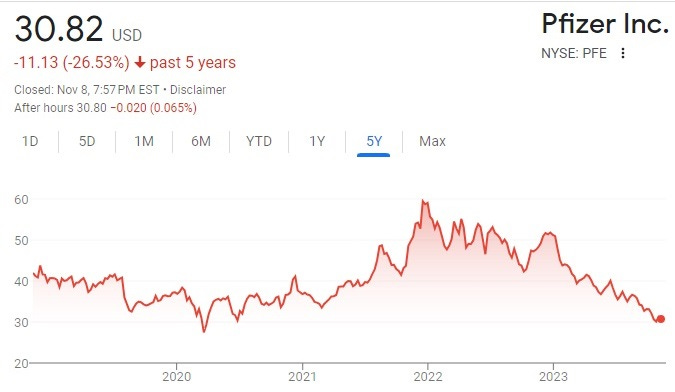

Pfizer’s stock price is lower than it was pre-covid, and the slide would look worse if the below graph accounted for said inflation.

It’s been encouraging to see the low uptake of the new mRNA jabs. If people can develop the same wisdom about the similar clinical irrelevance of America’s big-time prescription drugs—subtracting from this analysis, that is, the uniquely vicious extent of the jabs’ “side effects”—then we* can see this same glorious arc in the stock performances of other drug companies.

I looked a little more into Alex Kurt. It’s possible he doesn’t himself know that his story was commissioned for the purpose of serving a drug ad. If it wasn’t, the names of the statins he was or is on wouldn’t have been included. I think he’s just a typical oblivious American “healthcare” consumer who doesn’t blink at the idea of taking drugs that don’t have any proven therapeutic effect for years on end, then switching to or adding other similarly ineffectual drugs.

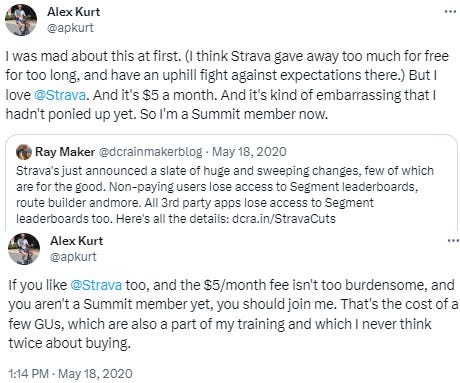

But if he was being deceptive rather than a garden-variety yutz in his “running is no panacea” story, beyond presenting the details of his medical history in a disingenuous order, this wouldn‘t be surprising. According to his LinkedIn profile, Kurt, in addition to writing for Trail Runner, works for Strava and used to work for HOKA ONE ONE. These are three of the most demoralized entities or companies in the sport. I bet Mr. Kurt knows exactly who HOKA sponsee and Strava heroine Latoya Snell is.

Statins aren’t the only useless or dangerous drugs Kurt has advocated for. At least that’s what I take from this passive-aggressive swipe (and for God’s sake, just tweet what you mean instead of being a passive-aggressive shitbird):

I don’t know when Kurt, whose Instagram account is set to private, started working for Strava. But perhaps this job was a reward for his pushing people on Twitter to sign up for paid Strava memberships, even going so far as to complain that Strava was giving away too much for free.

Kurt shilling for Gu is an odd choice, since this product offers around three-fourths of its nourishment from the artificial sugar maltodextrin. Eating “foods” like these has traditionally been framed as bad idea for pre-diabetic persons, but maybe that advice has changed along with everything else.

Kurt has also dabbled in the standard virtue-signaling and amplification of Wokish messages from the most obnoxious harpies and haters around.

Finally, like me, Kurt even has a history of bashing Outside as a company. But unlike me, he’s either sufficiently deluded to pretend Thurston has done anything but passively trash these publications by hiring as editors a suite of profoundly retarded snowflakes-of-privilege to do the active damage—laughingstocks and fuck-knuckles like the Roches and Zoe Rom who only exist because a modicum of well-off, slack-jawed narcissists annually decide to relocate to places Boulder and wander the trails and coffee shops in between sucking what there is of each other’s titties and dicks both online and off.

Also, while the following two stories clearly have nothing to do with Pfizer, ill-advised drugs, or anything else I’ve covered here, they deal with young runners who recently died as a result of previously unknown medical conditions. In fact, in just the past month, eleven Americans between the ages of 9 and 19 suffered heart attacks at school or during school-related activities.

Climate change is a real threat, folks!

As for Outside’s chances of succeeding as a public company, we might learn more about that soon enough. Around a year ago, Thurston claimed that Outside’s investors, enthusiastic in 2020 and 2021 but more tepid in 2022, wanted the company to stop posting losses by the fall of 2023 or else they wouldn’t be throwing any more venture capital his way.

That fall is now halfway over. All of Outside’s publications are worse than ever—a daily embarrassment of Wokish riches coupled to the most garbled and ignorant, yet somehow smug and self-serving, physiology chatter in the history of the genre. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re still losing money, because only about six people—all, to be sure, with eyes that move independently and brains that can be heard sloshing from one side of their skulls to the other when they quickly rotate their heads—now appear to be full-time employees of these publications.

But in at least trying to assure himself and his hopefully soon-to-be-woebegone investors a rosy financial future, Thurston is conspicuously keeping pace with the rest of the corporate media when it comes to the slinging of toxic medical advice, fever-dreams about reproductive physiology, anti-white-male scorn, and other dizzyingly stupid, inorganic, and desperately needless noise that gives everyday 2023 life the feel of a simulation assembled by a very creative but subversive deity on a slight excess of angel dust.