Recap of the final five Diamond League meets

Also, pros should be paid more prize money, especially if the stewards of the sport continue to spot-incentivize doping

I now dedicate just enough attention to professional distance running to remind myself why I continue to lose interest in professional distance running.

In the U.S., the sport’s governing body—already a longtime haven for cackling, jet-setting grifters—is entirely controlled by an appropriately sociopathic billionaire who just can’t have enough and funds a team plainly awash in dopers, one formally caught and the rest “undetected.” Meanwhile, as if to add a grisly element of balance to fast cheaters getting things they don’t deserve, slow or even motionless cheaters are getting free gear and race entries from shoe companies, major marathons, and the nation’s largest running organizations. The women’s category has come to include various men whom announcers are careful to call “she” as well as at least one lesbian who disavows her sex outright, requiring these same petrified and quietly disillusioned announcers to call her “they.”

All of this roiling decay is being duly “covered” by a Woke-bombed media riddled with mush-brained suck-ups and “feminists” who propel their quasi-recondite woman-envy with blatant science denial, and it’s being cheered on by former elites whose moral compasses point solely in the direction of virtue-signaling and self-interest (too many to link). The whole “It’s not about us, it’s about me!” show is about two Chris Chavez tweets from adopting Brawndo as its sole permitted in-competition beverage and the film that introduced it as the defining inspiration for the 2022 version of running culture.

And as the active degradation of fair competition proceeds at all competitive levels, the best distance runners in the world—doped-up and otherwise—are given breadcrumbs for prize money.

Nevertheless, I like reviewing what goes on in Diamond League races. World records are invariably threatened if not broken at a predictable handful of these meets; this gives me an excuse to both ramble on about names and races from a bygone century and complain that someone I dislike has replaced someone I like from the top an all-time performance list, exercises I greatly enjoy even when I have to invent the reasons for my biases on the spot or transparently found them in opportune grudges.

On August 28, I displayed my zirconium-caliber reporting when I made this announcement:

Three of the four post-World Championships meets on the 2022 Diamond League schedule have been held, with the final one scheduled for September 7 and 8 in Zurich.

The “four” in there should have been a “five.” Forgetting about the meeting on September 2 in Brussels, however, didn’t stop it from happening. Some impressions from these meets are below, followed by a summary of one of the sport’s serious problems that could be easily remedied.

Silesia, Poland, August 6: This meet had something of an undercard feel to it despite including plenty of superstars in the shorter running events. Maybe my bedroom was too dark. I took great interest in the women’s 3,000 meters, as the field included Sifan Hassan (personal best coming in: 8:18), Ejgayehu Taye (8:19, 14:12 5,000m in May), Margaret Kipkemboi (8:21, 29:50 road 10K) and others British observers would call “useful runners.” The pacing lights and human pacer(s) set off at 66-67 per lap, or 8:15-8:18 pace, but from the start the competitors had no interest in running fast.

The 2,000-meter split was 5:58. Not only is that not fast for a 3,000m, it’s not fast for a 5,000m and it’s not even close to world-record 10,000m pace. In fact, had Letesenbet Gidey run her 1:02:52 half-marathon last year on a track, each lap would have passed in very close to 71.5 seconds and she would have hit 2,000 meters in 5:57.5.

An equivalent scenario in a men’s race would see the men passing through 2,000 meters in 5:27, or 8:10 pace (the half-marathon world record is 57:31, which translates to 65.4 seconds per 400 meters. 8:10 is a yawn for a Diamond League 3,000-meter steeplechase.

But every time a women’s race 3,000 meters or longer unfolds, I view it through the lens of Gidey’s otherworldly 1:02:52 whether she’s in the race or not. The only reason she hasn’t destroyed a swath of records on the roads and on the track almost has to be that she’s being disallowed from that luxury in exchange for being allowed to dope without overly abusing the privilege. She should be able to run under 13:50 and 28:40 with comparative ease.

Then again, not that long ago, fellow Ethiopian Almaz Ayana, wherever she went, could have been the subject of almost the same conversation.

Monaco, Monaco, August 10: Recently anointed 1,500-meter world champion Jake Wightman showed just how fast Noah Ngeny’s twenty-three-year-old 1,000m world record is by winning in 2:13.88 and landing almost two seconds outside of Ngeny’s standard, with only two of the twelve finishers breaking 2:15.

Grant Fisher broke Bernard Lagat’s American record in the 3,000 meters with a 7:28.48 for third place. For purists, Fisher was born in Canada and runs for the Bowerman Track Club, and Lagat was born in Kenya, at one point secretly keeping his citizenship foot in that nation’s door, and later failed a drug test. So, Bob Kennedy’s 7:30.84 from 1998 is looking from here like the best all-factors-considered performance by an American over 3,000 meters outdoors.

Faith Kipyegon flirted with the world record and 3:50 in the women’s 1,500 meters and just missed both. She won the race by over eight seconds, with the U.S.A.’s Heather MacLean second in 3:58.89. Twelve American women have now broken four minutes for the distance outdoors, with five of them recording their current personal bests in 2021 or 2022 (all-time U.S. list).

Lausanne, Switzerland, August 26: Jakob Ingebrigtsen has decided that his best strategy in 1,500-meter races is to run as close to even 3:29 pace as possible, and it seems to work well most of the time. He broke 3:30 for the second time in 2022 and the fifth time in his career by running the year’s then-fastest time, 3:29.05.

Gangly-ass Soufiane El Bakkali won the steeplechase by nearly ten seconds in 8:02.45. It’s got to be hard keeping the pressure on with a huge lead in that event, but this guy does it while practically blowing kisses to the crowd, which in turn later tests positive in bulk for EPO.

In the mostly women’s 3,000 meters, Francine Niyonsaba (8:26.80) towed Alicia Monson of the United States to an 8:26.81, good for first among potential birthing people and the second-fastest time ever by an American (Mary Slaney’s 8:25.83 tops the list). Superspikes or not, how Monson gets it done with that lurching, almost ungainly style is anyone’s guess. She doesn’t give anyone an inch except when the leaders of whatever race she’s in make ill-advised or impossible-to-match surges.

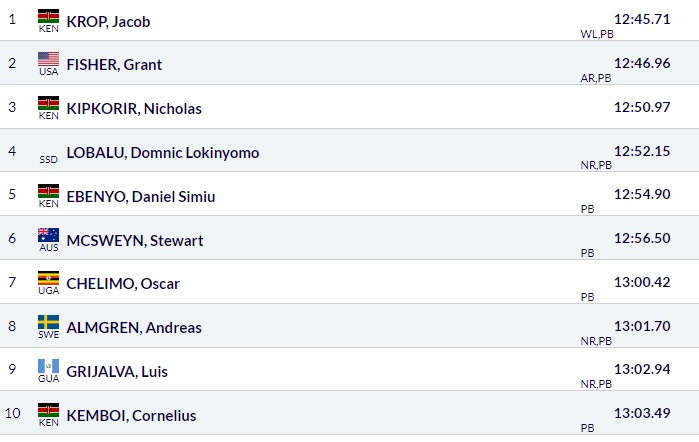

Brussels, Belgium, September 2: The held a men’s 5,000 meters here. Nine of the top ten set personal bests, and four of those men set national records. One of them was Fisher, who broke another of Lagat’s American records, this time by over six and a half seconds.

Fisher’s performance wasn’t a surprise given his 12:53 indoors earlier this year and the 7:28.48 3,000 meters he ran less than a month earlier. But seeing 12:46.96 next to his name was still hard to process.

The women’s 1,500 meters saw a temporarily confusing Irish national record set by Clara Mageean (3:56.63). Mageean is from Northern Ireland, but athletes from that part of the “United” Kingdom have the option of competing for Ireland. That some folks choose to do so is entirely unsurprising, but I was among those who had never considered such a scenario and hence the availability of a choice. When I was nine or ten, there was a period of near-continuous news footage of Molotov cocktails flying through windows in the Belfast night. That’s one brand of violence that seems to have blessedly disappeared, though it would be a nice gesture for King Charles to give Ireland its whole island back by Howdy Doody-esque fiat.

Zurich, Switzerland, September 7 and 8: Noah Lyles wound up dominating the 200 meters this summer. I thought Erriyon Knighton would beat him at least once this year, but Lyles was consistently around 19.50.

Ingebrigtsen ran a virtual repeat of his Lausanne race in the 1,500 meters, coming home 0.03 faster here (3:29.02) than there and bumping himself to number two on the 2022 list. I hope he takes the same tactics to the 5,000 meters if he moves to that event full-time.

Sha’Carri Richardson’s season came to a disappointing end. Maybe she should consider a coaching change. Richardson’s 2022 times seemed to fluctuate more with wind direction than the magnitude of the breezes affecting her races would imply. In eleven 100-meter dashes this year, she experienced five headwinds, running over 11 seconds in all five of those races, and six tailwinds, running under 11 seconds five times out of six.

Now for some brief commentary on how the profits (or at least revenues) being made in track and field could be better shared.

In July, an article in the L.A. Times detailed plans for a Diamond League-like set of five track meets in the United States next summer, with this being part of an aim to boost track and field’s popularity in advance of the 2028 Summer Olympics, which were quite insanely awarded for the third time in history to the same dismal city in the U.S. enclave of California. It seems like a good idea.

The image below captures most of the salient text.

In case you were wondering what the Diamond League circuit is all about, and why World Athletics thinks it makes sense to plop the World Championships right in the middle of the schedule, here’s the points structure and money breakdown. A total of less than $1 million was awarded to the thirty-two individual winners this year.

If NBC, Phil Knight, and USA Track and Field are all for getting fans interested in track and field, why not make it more interesting for the athletes by paying them more? Why isn’t a portion of NBC’s streaming revenue allotted to athletes every time a contract is signed?

Obviously, Knight himself could kick in $10 million without blinking to a general prize fund that would pay the winners and top placers at the meets next summer in the U.S., but he wouldn’t do that unless he could pick all the winners in advance instead of just most of them. And it’s not his job anyway, unless one considers him the de facto president of USATF, an organization with its own money to burn (and it essentially does exactly that).

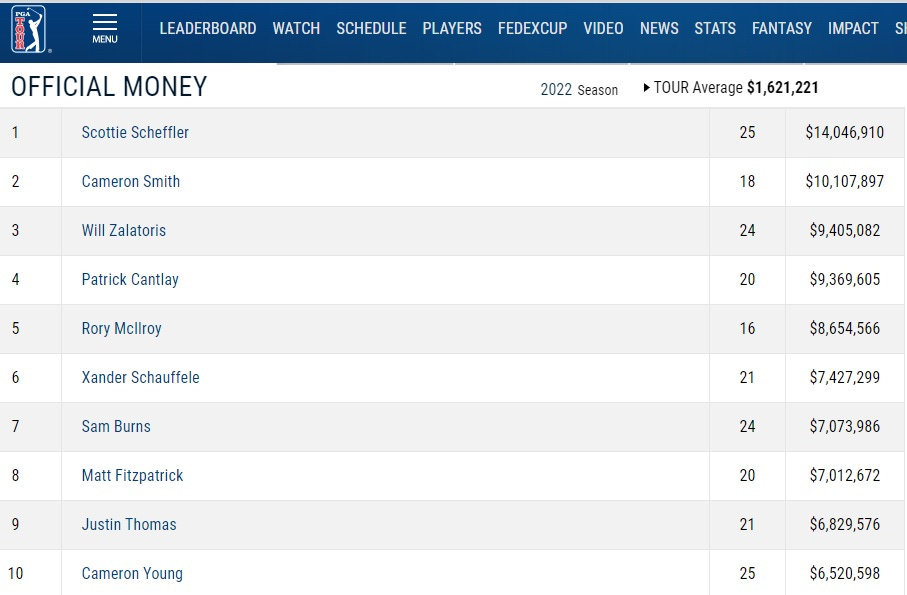

Maybe track and field needs to somehow market itself to the kind of people known to utilize the services offered by money managers and other financial professionals—i.e., rich people who watch golf. Scottie Scheffler won fourteen times more prize money by himself in the recently concluded 2021-2022 season than the thirty-two Diamond League final champions combined. One hundred and twenty-six golfers cleared a million dollars.

(Nineteen women earned over a million dollars on the LPGA Tour in the same period, with Minjee Lee the leader at $3.742,440.)

Professional track has the problem of incentivizing doping (or if you prefer, selectively punishing it) while also ensuring that only a handful of athletes earn any real money outside of their contracts, which are often dog shit. The best deal I know of for a distance type is $12 million over twelve years, and the company is almost certain to earn a superior ROI from this athlete. More asses in stadium seats would help, but a lot of people rely on and even hunger for those NBC/Peacock broadcasts and would enjoy knowing that athletes were assured a certain portion of the revenue. Better yet, athletes would get that money.

(I could propose a host of reasons why shoe companies vastly prefer that athletes rely heavily on their dog shit contracts, but I would rather end on a noncommittal note than an openly inflammatory one.)