Starting every June or so, generally trustworthy marathon-training advice starts to fail thousands of fit and motivated runners

Most summer long-run and other heat-adaptation strategies aimed at achiever-joggers may not make the required environmental concessions

About half an hour the first Rosie-free (and hence, solo) run I did after discovering that the over three dozen articles, interviews, and other tidbits I authored and assembled for Running Times Magazine between 1999 and 2015 had been removed from the website of the entity that inherited this work, I felt an unanticipated sense of renewed interest in my own thoughts about training and other matters revolving around optional modes of sustained human scampering. Although no representatives of the triumphantly demoralized inheriting-entity, Runner’s World, contacted me about this decision—or for that matter responded to any of the questions I had recently asked its staffers that, along with the Beck of the Pack posts those same staffers haplessly rage-read, surely triggered the deletion of my articles—I realized that I had come into sudden sole possession of a horde of information, or at least words, that were by definition and formulated for sharing with others and free of distracting side-chatter (and sentences as lengthy as either of the two forming this entire paragraph, with this one being the decisively more ornate, lavender, and intrusive).

From a practical standpoint, absolutely nothing has changed, as I haven’t heard a peep from anyone about any of those now-vanished pieces in years. But with my eyes having been given reason to scan the titles of thirty-odd articles that were now far harder to locate online, I found myself reconsidering some of that work and whether my perspectives had changed substantially on any of its “technical” points; after all, anything useful I uncovered in explorations of this content would surely be worth writing about.

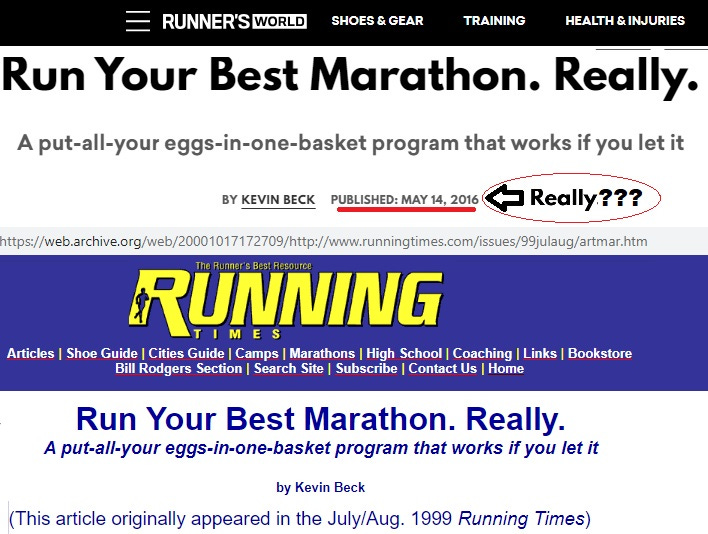

The single article that sometime in late 2000 most likely inspired Running Times editor-in-chief Gordon Bakoulis to name me a contributing editor and then a senior writer—both nothing more than masthead titles, but still strong upvotes from a reliable source—was “Run Your Best Marathon. Really,” which Gordon assigned the subhead “A put-all-your eggs-in-one-basket program that works if you let it.” This really is the perfect encapsulation of the material, and not what I would have supplied if asked to produce a subhead for the piece myself.

When this article was published in the July/August 1999 issue of Running Times, the corresponding website was under construction1 and the principals of the business, along with the heads of every other print magazine, were trying to figure out how much past and current magazine content should be available online—and whether any of this would even add value to the enterprise. As hard as it is for some to believe now, online advertising was a venture with mostly unproven and uncertain returns in those days, as an October 20, 2000 snapshot of the Running Times homepage affirms.

It’s fair to say that, by the standards of the day, the article went viral. Meaning, it generated a lot of e-mail traffic and mentions on message-boards, which were then the only means of allowing hundreds or thousands of users to participate in the same more-or-less-real-time conversations. Social-media sites, even MySpace.com, were still years away from their ignominious stepwise insinuation into public, private, and imaginary lives.

I don’t know how good my stuff actually was, but the market was very limited in those days. You couldn’t just send off an e-mail that read “Hi, Black af here & I have a proposal about restorative queer-beer-mile justice, see links below thx” and expect an assignment. And until sometime around the onset of the Iraq War, you couldn’t just ask the Internet a question and get a pile of mostly helpful resources. (Despite the ease of doing such research today, none of the current editors and freelancers with any name recognition ever seem to do any of it; this crew already has all the answers, facts notwithstanding, and its members are here to educate us geezers and their fellow pimple-poppers alike.)

At the time the article was published, I wasn’t yet even a sub-2:30:00 performer at the distance of interest. But the advice in this article formed the basis of my own training for the rest of my competitive days, which ended with me being a 2:24:17 performer, and has formed the meat of all of the training plans I have ever conceived for other marathon runners. I didn’t invent the “MP run,” but for whatever reason it had only been popular among elite runners outside the United States until the end of the twentieth century. I’m sure plenty of old-timers were quietly doing them as early as the 1970s, among them many people who have probably never taken or needed a single element of advice offered in a magazine.

Someone who lives in a hot, swampy part of the U.S. and is considering a fall marathon asked me a question the other day about how she should structure her training. This is someone who by constitution is unusually sensitive to hot-and-muggy weather and whose work schedule puts the kibosh on most standard work-arounds.

Most North American runners who focus on completing marathon races as quickly as possible, and run only one marathon a year, choose a fall marathon; runners who do two marathons a year with one in the fall generally assume the later race will offer a better chance of a faster time. Those who do three a year—and this has become somewhat more common among genuine elites—almost always pick one in the spring and two in the fall. Anyone running more than three marathons a year is probably not especially focused on running any of them as fast as their bodies might allow them to with the right training.

The implication of this Northern Hemisphere reality is that most serious marathoners are deep into their specific preparation by the beginning of August at the very latest. This in turn means that, for many of these runners, it will be a lot warmer—and when you see “warmth” in a running context, think not just direct sunshine and air temperature but other misery indices such as dew point—for key workouts no matter what time of day they do them. When I lived in South Florida for a couple of years (don’t ask), I could have run at 4 a.m. in July or August and it still would have been in the low seventies eighties Fahrenheit with crushing humidity, whereas most people can safely plan on goal-marathon-day temperatures well below 70 degrees and dry-enough air.

Summer is a real problem for competitive marathon runners, especially those especially beaten down by whatever version of this season they’re immersed in. This is because marathon-pace runs are both vital and impossible for some people to do without losing more from the effort than they gain, even with significant modifications to the original pacing plan.

I have made dozens of attempts over the years to create bespoke schedules for runners training in hot summers for cool-weather marathons, and it appears that some people just can’t train very effectively above a certain point of thermal stress (combination of temperature and humidity). Some runners struggle so much in standard American summers—not just in Florida, but ranging up to around 40 degrees North latitude—that workouts like marathon-pace runs become impossible to suitably amend without simply giving up and replacing them with something else. What the “something else” consists of is not so much a matter of how willing a runner is to suffer in order to secure fitness gains as it is of how willing a runner is to suffer for the sheer fuck of it with no real promise of remotely proportional fitness gains.

And when I say that some runners “suffer” or “struggle” far more in the heat than others do, I’m not merely observing that some runners complain more or show consistently poor results compared to others in hot-weather workouts and competitions. In some cases, this can be measured. Human sweat rates vary widely; although in general a more heavier person will lose more fluid per unit time than a lighter person, all else being the same, I’ve known runners no heavier than 50 kilograms (110 pounds), usually men, who lose fluid so rapidly when even jogging in the heat that they almost might as well be barfing up whatever they drink on the go out of their primary face-pore rather than distributing the leakage across their skin-pores.

The physiological traits that engender what we* term “heat tolerance” are probably as heritable and poly-allelic (i.e., arising from not one DNA sequence but many, some neighboring and mutually influential, others located on different chromosomes) as the traits we perceive as “endurance talent.” Just as susceptibility to covid-19 and other infectious diseases can usually be mapped onto the genome with the right analytical tools, the extent to which people flail when trying to run hard in warm environments is not just highly variable but largely unmodifiable. Everyone can become better acclimated than he or she is in midwinter, but to some people, 85 or 90 degrees with high humidity won’t just seem “really hot.” It will feel like training in Singapore or Tripoli. And it’s not a mental thing.

When runners are training for races no longer than, say, 10K or about 45 minutes, it’s easy enough to modify repetition workouts and even shorter tempo runs based on the conditions, because both individual reps and the workouts themselves are volume-limited. But I have learned that when it comes to sustained efforts of even half an hour, let alone the two hours necessary for some runners to complete long marathon-pace runs, it’s not possible to just look at the weather report and say, “Okay, slow down by 15 seconds a mile.”

For one thing, even if I guess someone’s “heat compensation factor” right when it comes to a given workout—and heart rates are a useful rough guide for this stuff, but no more than that when the warmth-misery factor is high—this won’t necessarily work for a different, similarly fit runner in the same conditions, and it may not work for the same runner every time. For another, running even remotely hard in serious heat or merely high humidity is extremely taxing, and women may face marked fluctuations in heat tolerance throughout their menstrual cycles:

[S]ubstantial evidence exists to suggest that increased progesterone levels during the luteal phase cause increases in both core and skin temperatures and alter the temperature at which sweating begins during exposure to both ambient and hot environments.

If you live someplace where running your legitimate marathon pace for even 10K feels like a race, even at 4 a.m., your options are limited. You may have access to a treadmill in a somewhat cooler environment, especially if you’re among my many wealthy friend and benefactors. You can try running back and forth on a fully shaded section of path if forced to run while the sun is glaring at you from whatever malign strip of sky it’s traversing while you’re out there.

Otherwise, these kinds of runs are just not worth it. This is especially true for those who cannot do more than, say, 50 miles a week (or an hour or so per day) of training. If you’re intent on doing a fall marathon and have a time goal in mind, but have no realistic chance of doing sustained runs at a hard or hard-ish pace, you’re better off conceding the intensity wars and just doing multi-hour runs at about 70 to 75 percent of maximum heart rate. If you do these on a treadmill, it’s easier to drink water and (one hopes; ceilings vary) avoid direct sunlight, but it’s also easier to begin hating, in sequence, running, marathons, yourself, and the good God above.

I believe that maintaining cadence while running slowly is a better bet than allowing yourself to shuffle along at 150 to 160 steps per minute at the pace this intensity level is associated with, especially when exposing yourself to intravaginal-like training settings. Pitter-pattering along makes both a slow long run feel like less drudgery and—I’m convinced, albeit on no common evidence—makes racing in the absence of speedwork less of an unmitigated, whooping disaster. Also, if you feel like absolute crap, take breaks. This is not always—or for veterans, even often—a sign of inadequate fitness, anyway.

If you cannot actually find someone who is slower than you are yet fit enough to do genuine long runs in peri-scrotal climes, one helpful mental trick is to pretend you are doing your long run with such a person alongside. When you feel like stopping going up a hill, do you need to stop or do you just need to slow down a bit for your “friend”? By the way, it’s generally not a wise idea to talk to this nonexistent, if cooperative and game, companion or otherwise visibly interact with whatever and whomever you think this runner looks and sounds like. Even if you don’t end up with heat stroke, a witness is likely to believe you’re already in the throes of it and force you into the nearest hospital emergency room. And if you get sent to a hospital anywhere in the U.S., especially when fully healthy, you’ll be a lot worse off when you bumble out of its doors into the muggy air that awaits.

I will get around to more posts in this style as the mood strikes and as time permits, although I cannot promise these will be any more focused than this one is, even if none will require the preliminary rambling this one did.

The domain name runningtimes.com had been bought by the cybersquatty douchebags who owned coolrunning.com, which did indeed have a cool-enough run before the even worse douchebags who owned Active.com—a digital simulacrum of gastroesophageal cancer in the approximate shape of a Web domain—bought Cool Running in 2008 or so, around the same time Runner’s World ingested Running Times.