The Mount Washington Road Race should institute doping controls, just to be on the safe side

This one is pure comedy, turning "dirty af" into a double entendre

After last year’s Mount Washington Road Race, I wrote about the “weird results profiles” of the top two women’s finishers, Kim Dobson and Amber Cullen-Ferreira. By “weird,” I obviously meant “unlikely to be produced by runners not using banned substances.” If I tempered my suspicions at all, it was because the race to the top of the highest peak in the Northeastern U.S., normally 7.6 miles long, was shortened by half in 2022 owing to inclement weather, making it hard to get a precise read on how fast Dobson, Cullen, and the rest of field would have performed under typical conditions.

The 2023 MWRR was yesterday, and it went the full 7.6 miles. Conditions were drizzly and foggy with a wind-chill reading of 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Dobson didn’t run, and Cullen-Ferreira, 41, took the win in 1:15:16, giving her a cushion of 47 seconds over Marybeth Chelanga. Chelanga, 33, is the wife of Sam Chelanga, who was second himself in the men’s race to 39-year-old Joe Gray, now a seven-time MWRR winner. Marybeth ran 33:59 for 10,000 meters on the track on March 4, while Sam, who’s 38 and has PRs of 13:04 for 5,000 meters and 27:04 for 10,000 meters, ran 27:34 in the men’s 10,000 meters at the same meet.

The MWRR was canceled in 2020. Cullen-Ferriera had a baby girl in August 2021, so she would have been around seven months pregnant for the 2021 version. Her pre-”pandemic,” pre-pregnancy results at the event:

When Cullen-Ferriera ran 34:29 last year, I speculated (with Dave Dunham’s help) that this might have translated to 1:14 for the full distance in decent weather. Her 1:15:16 yesterday probably would have, too, although a drizzle and some chilly fog would be considered fine weather given what can happen toward the summit of that crazy mountain even in mid-June.

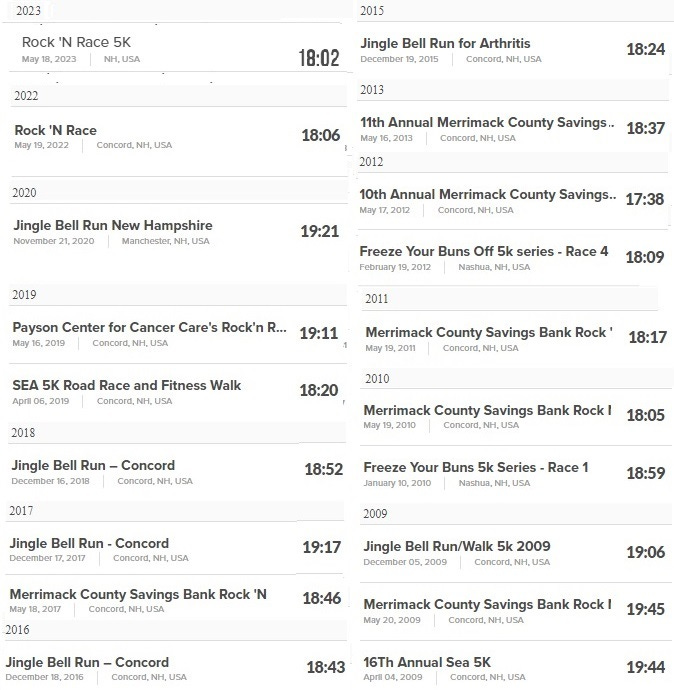

As I described at this time a year ago, Cullen-Ferreira is not someone who was a casual runner pre-covid and then used the down-time to put unprecedented levels of training. She began doing Ironman Triathlons in 2009 and evidently isn’t done with them yet. You can see from the data below, collected from Athlinks, that she gradually became faster over the next four years, then gradually started slowing down until she was back to about where she started.

I decided to check to see if the arc of Cullen-Ferreira’s 5K times correlated at all with that of her Ironman times. It does.

In 2009, for example, she ran 19:45 at a late-May 5K in Concord, N.H. her place of residence and my hometown. The race has changed names a few times, but as you can see, Cullen-Ferreira ran 18:05 in 2010, 18:17 in 2011, and 17:38 in 2012 before gradually slipping back into the low 19’s. Then—post-pregnancy, post-covid, and past her fortieth birthday—she ran 18:02 in 2022 and 18:06 last month.

It seems that Cullen-Ferreira’s MWWR fitness should closely track that of her overall racing fitness. So how does someone who’s been working her aerobic system relentlessly for close to two decades find a way to get significantly faster at 40, at anything?

You guessed it—mommy power!

This woman virtually has to be using multiple banned substances. This would be easy to conclude even without all the typical boxes checked off—she’s triathlete, she makes a living by coaching, she loves attention, she loves to win, and in her early forties she’s desperate to hold on to her ability to win.

What a crock.