The publication of Kara Goucher's book could serve as a turning point in professional running, but it won't

Also, I look pretty stupid, depending on how far, and how far back, people read

Retired professional runner Kara Goucher’s book The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running was published on Tuesday. This book—not Goucher’s first—has been described as “long-awaited,” and the wait may have in fact been too long for cogent running fans to believe that it will change anything about the culture or administration of professional distance running. Nike has gotten away with far too much in the past eight years for any broad moral “reckoning” to occur.

I have not read the book, but I am aware of its chief revelations. One is that it appears indisputable, or uncontested, at this point that Goucher is a victim of sexual assault by Alberto Salazar, even if he may never have a criminal conviction on his record as a result.

In October 2021, I wrote a post that stands as one of the most-read on this site since my August 2020 move from Blogspot to Substack. Taking into consideration recent tidings, the title makes the author look less than reliable.

In that post, I argue that once someone commits to trying to be among the world’s best runners, he or she commits to an environment rich in rule-breaking and directives that, in everyday contexts, would in fact constitute abuse or at least maniacal overreach. A coach ordering a 15-year-old to keep his or her weight below 100 pounds is always abuse, in my view, no matter how fast or promising the kid is. Demanding the same of a 30:00 female 10,000-meter runner is routine, even if it’s almost as discomfiting to observers at a visceral level. If Sifan Hassan’s coach told her to lose a few pounds, she’d surely go for it even if it turned out to be the wrong move, competitively or health-wise.

Considering that the title of Goucher’s book contains the words “secret world of abuse, doping, and deception,” I don’t think Goucher or anyone who has reached her level in a group setting would disagree with this idea.

That flawed post included this passage:

The U.S. Center for Safesport, created in 2017 mainly to respond to allegations of sexual abuse by coaches of younger athletes, placed Salazar on its “permanently banned” list this past summer, a move that may prove to have no real teeth.

Not long after I published this, I began to hear rumors that Salazar had digitally raped someone in the course of “giving a massage.” It immediately became clear who the alleged victim was. I declined to mention this here because the case was making its way through SafeSport—not to protect Salazar, but because mentioning the names of sexual-assault victims before victims themselves come forward is ugly no matter how obvious the particulars may seem or who else is discussing them.

Either way, that title looks bad. Despite the content of the post itself being mostly about discretionary “abuse,” if I saw that in a Google search result, I would discard the writer as a dunce and either not click on it at all or click on it expecting to find someone or something to deride. So, even though everyone knows writers usually don’t generate their own headlines, mea culpa.

And I hope I haven’t come across as defending Salazar’s overall character. That would be unlikely, considering that in 2015, writing on Blogspot in posts since automatically imported to this domain, I firmly sided with Kara Goucher.

Because by 2021 I had heard from athletes formerly coached by Salazar who didn’t see him as abusive, just perhaps not everyone’s ideal choice of mentor, I had settled on the idea that Salazar was generally a Machiavellian asshole who doped as many of his runners as he could get away with, and told already lean runners to lose weight. But I coupled this to the sad reality that anyone who wants to survive in an environment like that of the Nike Oregon Project has to put up with those things, hopefully without suggesting that this is automatically or even ever the right choice.

Kara Goucher is retired, but of her own volition has remained extremely active in running as a commentator, podcast host, social-media gadabout, and hypothetical anti-doping advocate. I say “hypothetical” because Goucher refused upon direct challenge in a podcast to openly state that she believed that the already-banned Nike Bowerman Track Club athlete Shelby Houlihan had intentionally used banned substances, a stance I find it difficult to believe she truly holds (go to the 35:45 mark here). In refusing to be forcefully judgmental, she was keeping at least one toe in the mass denial of intentional cheating by Houlihan; at least she acknowledged her own intractable bias.

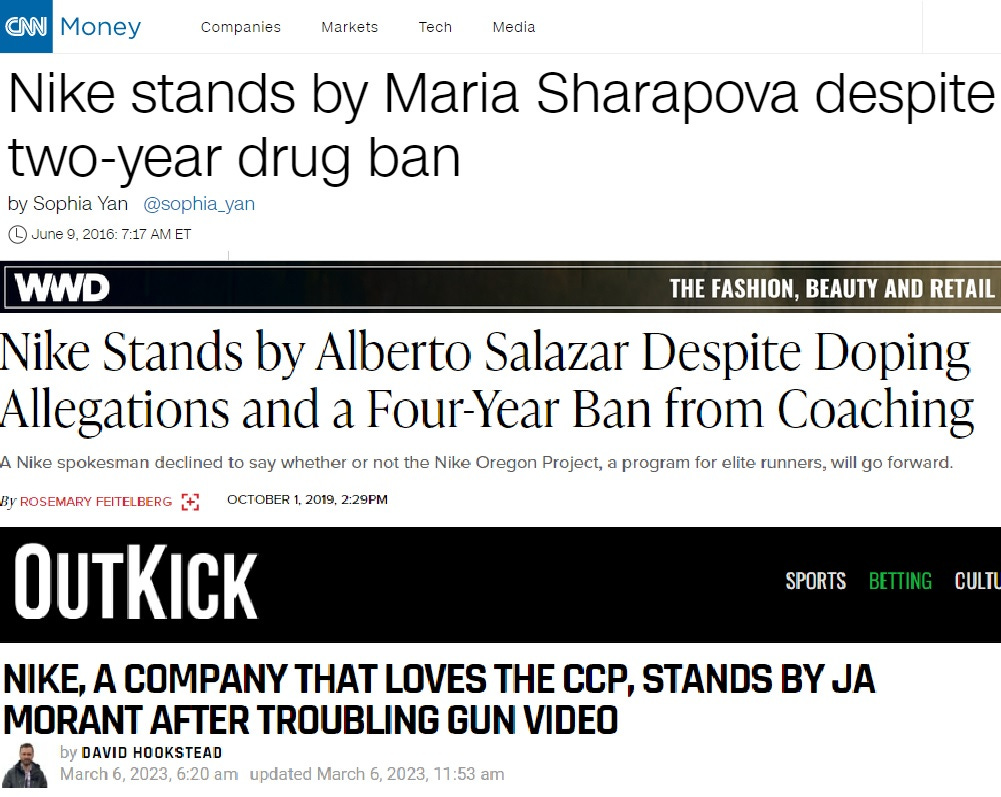

And that gets at something I’m not sure people understand yet, despite what the title of Goucher’s book attempts to illustrate: While running, like any sport, is “dirty” almost by obligation, Nike is an especially diabolical player. Salazar’s mistake, from a corporate stance, wasn’t operating a doping program or being a hard-ass coach. It was being a dirtbag even in context, because even Nike can’t make digital rape look good.

The reviews of the book from both within and outside the running media are laughable. This one is written by someone who recently speculated that separating sports by sex makes no sense. And the oblivious incoherence of mostly literate pundits like the grimly hilarious Emilia Benton is endemic throughout running’s blinkered collective consciousness:

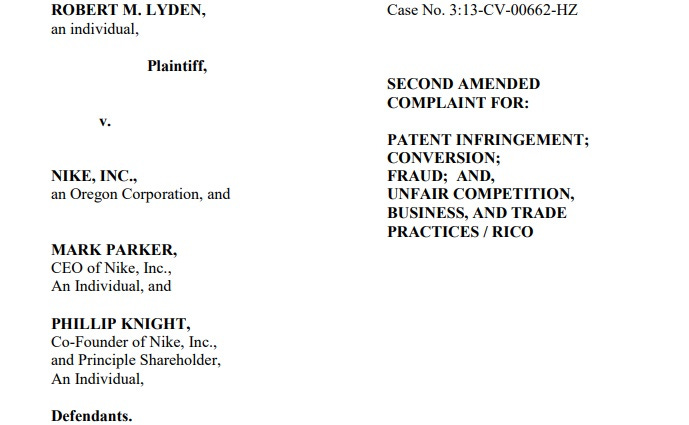

Nike is a bad problem for everyone. It always has been. I encourage everyone to read this December 2013 court filing. Some of the names are familiar to old-timers.

No one around in the 1980s or 1990s thought Alberto Salazar was running clean. He was desperate to win—why would he bother? I don’t know what they thought of him otherwise, but it’s unlikely anyone saw him one day earning the label of sexual abuser. In my experience, any Roman Catholic already known to be shady who talks about God a lot has a far higher probability than most people of eventually sticking a finger or penis into someone without invitation, traditionally a far younger person under the Catholic’s control. But that’s easy to say now.

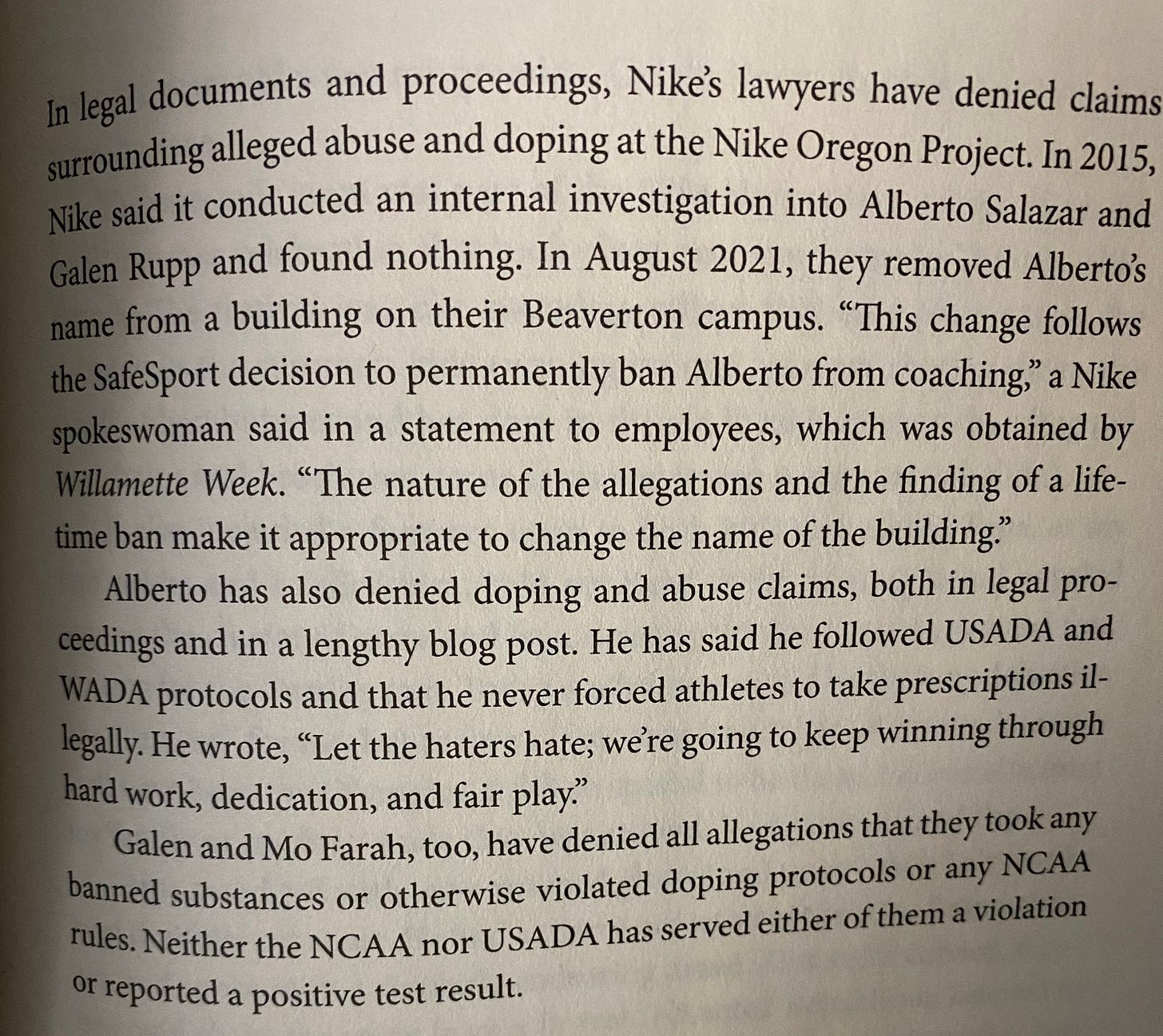

Again, I haven’t read the book. But what’s below is as close as Kara Goucher is legally allowed to come to accusing Galen Rupp and Mo Farah of doping—practically a formality, but significant.

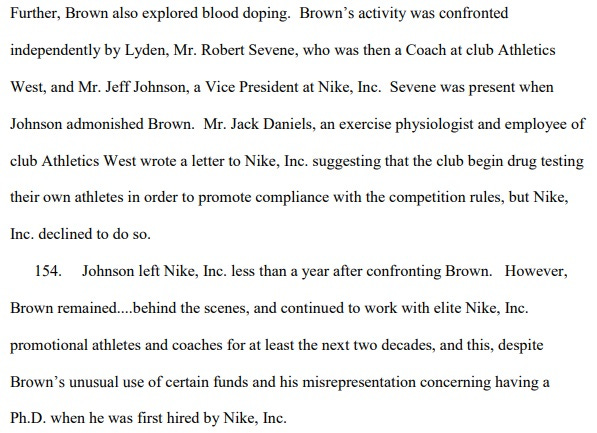

One somewhat confusing aspect in light of recent Goucher statements is the involvement of disgraced (but very active) endocrinologist Jeffrey Brown (that’s the Brown named in the above lawsuit) in Mark Wetmore’s University of Colorado program when Kara and Adam Goucher were members of the team. In fact, the Gouchers are who connected Brown to Salazar in the first place.

By 2019, Wetmore believed that Brown had earned a lifetime ban from the sport, but Wetmore’s comments about his relationship with Brown are reminiscent of Tony Fauci’s comments about his relationship with Wuhan biolabs. They basically imply that either the Gouchers are liars (or have poor memories) or Wetmore himself is lying (or selectively amnestic).

Both Gouchers recently took to Instagram to condemn an article in Runner’s World on the eve of the 2022 NCAA Cross-Country Championships implying that the University of Colorado program was an especially fulminant locus of body-monitoring-induced eating disorders and other problems. Although the Gouchers were rightfully panning a woefully unbalanced account, they were also delegitimizing the story of the young woman at the center of the RW hit-job.

It seems inconsistent to me that anyone would vigorously defend the methods of a collegiate coach who was apparently in contact with thyroxine-dispensing slimming merchants while they were running for that coach over twenty years earlier. Maybe Wetmore really did wash his hands of Brown. But the Gouchers couldn’t have disliked Brown much if they introduced him to Salazar once they joined the Nike Oregon Project.

The Bowerman Track Club has been more formally scandalized than its de facto predecessor in Portland, the NOP, ever was. The BTC has had one athlete suspended and at least one other depart owing to—she says—the suspended athlete’s continued intimate involvement with the BTC’s staff. All of them are demoralized, and everyone involved in the club has been subsumed into degeneracy, with the solace being that it’s always been this way.

It would be really interesting to see Goucher’s first draft, and I don't mean to see how the grammar and syntax and overall style evolved, but to see what material was nixed pre-publication. As soon as Nike got wind she was officially working on this memoir, it surely commissioned an army of eagerly demoralized attorneys just to manage what she was allowed to reveal or claim. I have no idea if or how any past nondisclosure agreements she signed still apply; as Keith Richards would say, “I'm out of whack here, this is serious lawyer shit.”

Goucher has been through a lot—as an athlete, a woman, a businessperson, a wife, and a mother. But it would be loopy to say that professional running destroyed her. She is welcome wherever in the sport she goes (well, maybe not all of Oregon) and is clearly enthusiastic about maintaining a visible and mostly cheerful role.

Ignoring the fact that I haven’t read the text, I would suggest that this book is as loud a cry to outsiders that professional running is endemically and perpetually corrupt as anyone is likely to make in the years to come. Stripping away any excessive framing of herself as a victim of athletic abuse—she was paid well to run for a living, after all, but Goucher is an affluent white woman and this is 2023, so her editors would have demanded this framing—the lesson here is that if you follow pro running, you are following a clown show.

The players are not all clowns, just pawns—clown shows, in this model, feature games of chess—and sometimes pawns can do heroic things both in combat and from the sidelines after their time as soldiers is over. Occasionally they can knock out a rook, or in the case of Salazar more of a knave, but only if the opposing player makes a really bad move on his or her own.

But they will never seize power from the kings.