Keira D'Amato just enjoyed the highest training ROI in distance-running history

Everything she's told the media about her training agrees with her Strava data. That data paints a picture of an unprecedented marathon runner

Anyone who read my last post about Keira D’Amato can see that, the title notwithstanding, it doesn’t propose that she got into 2:19:12 marathon shape by running a string of monotonic eight-mile days last year. I was accused of doing almost exactly that, but I thought it was important to emphasize in a straightforward way that D’Amato had just run a faster marathon than any American woman in history despite logging fewer than 3,000 miles in the preceding year. I doubt that any woman on Earth has ever done that or even come within a few minutes of 2:20:00 on such limited volume.

This is not a knock on D’Amato’s level of motivation—she was hurt at least once last year, and she averaged well over 100 miles a week in her build-up to a 2:22:56 at the Marathon Project in December 2020. Also, after someone reaches the American record level, it makes little sense to suggest that she or her handlers didn’t know what they were doing. But her relative paucity of training miles is a numerical fact, one she willingly offers to the public to do as it will. It makes her a natural object of curiosity.

This apparent disconnect between training input and race-course output led me to think that D’Amato, either through benign neglect or strategic shenanigans, may not have uploaded a substantial chunk of her 2021 aerobic training to her Strava account. I have no emotional attachment to records or who holds them. But when any outlier of this magnitude appears, my mind wants the contributing factors to resemble the ones that have produced comparable performances in the past. Because I associate 2:19 marathons by women with consistent, recent, triple-digit mileage, I have a strong intellectual desire to believe that she trained more than she did.

This doesn’t seem to be the case. Everything the media has reported about D’Amato’s training from D’Amato herself coheres nicely with her Strava data.

D’Amato first attained media prominence in June 2020 after running a 15:04 5,000-meter time trial. A Runner’s World story four days later included the following (emphasis in all quoted material mine):

In her 30s, D’Amato began working toward achieving her unfinished business on the roads and track. She has been running between 100 and 130 miles per week to train for marathons the past few years, squeezing in the miles around her jam-packed schedule as a realtor and mom. She qualified for the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials by running 2:34:55 at the 2019 Berlin Marathon.

After the Trials—she finished 15th in 2:34:24—she spent a few weeks doing low mileage, then brought her volume back up to between 60 and 100 miles per week this spring. In a typical month, she’ll run one week of 70 miles, one of 80, one of 90, and one of 100, then repeat the cycle.

(From the same story: “She isn’t sponsored; she has always purchased her own gear and paid her way for races. But she doesn’t mind. ‘I’d be open to a partnership, but I’ve had success on my own, and I don’t want to rock the boat.’”)

A week and a half later, Outside Online interviewed D’Amato. The author describes what happened after D’Amato finished the 2017 Richmond Marathon, a mid-November race, in 2:47.

D’Amato upped her weekly mileage to top out between 100 and 130 miles per week with one track workout, one tempo run and the rest filled in with “fun miles,” which can mean 6:30 pace or eight to nine-minute mile pace depending on the day.

This regimen is reportedly what got D’Amato to 2:34:55 in September 2019 in Berlin and a 15th-place finish at the 2020 U.S. Olympic Trials five months later in 2:34:24 (on a far tougher course).

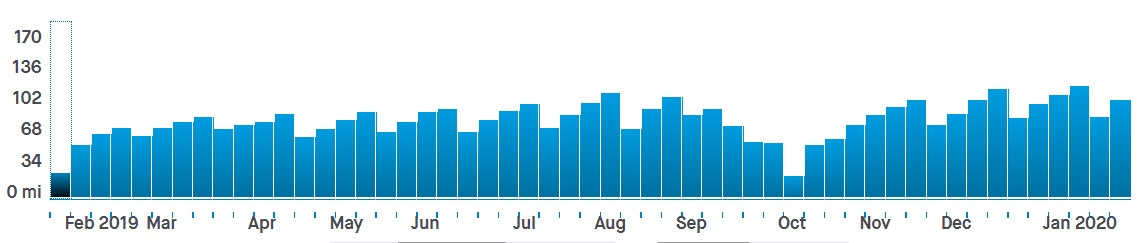

D’Amato’s Strava profile shows her topping 100 miles in a week only once in 2018, when she averaged 62 miles per week for the year. She ran a 1:16:32 half in March, 2:56:44 in the miserable weather at Boston the next month, and 2:44:04 at Grandma’s Marathon in June.

But in 2019, D’Amato recorded four weeks of over 100 miles before the Berlin Marathon in late September, with a high of 112. Her training log spells a series of six or seven faithful four-week cycles of increasing in-cycle mileage. Then, in preparing for the Olympic Trials in late February, she relied on the same rhythm, but with around 100 additional miles in every four-week cycle.

After the Trials, D’Amato shifted her focus.

With the idea of competing in the 10K at next year’s U.S. Olympic Trials for track and field, D’Amato and Raczko cut down her mileage to between 70 and 100 miles per week and added long speed workouts with short reps of 200 to 400 meter sprints.

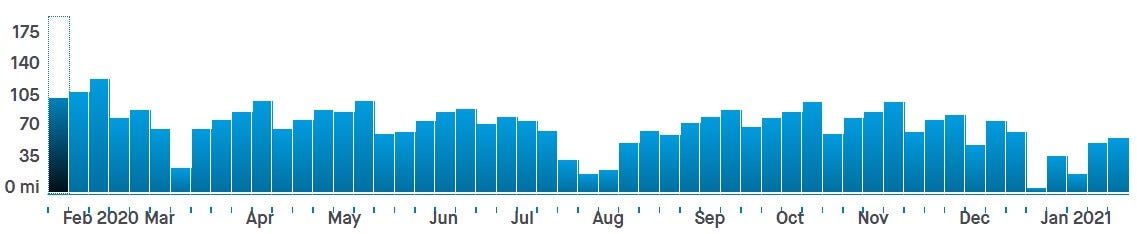

2020 is the year D’Amato became legitimately fast. She ran 51:23 for ten miles in October to set the women’s-only world record for the distance, in a fall that had already seen her run 1:08:57 for a half-marathon (World Athletics doesn’t acknowledge the performance as legitimate even though it was on a loop course) and 15:08 for 5K. Then in December she ran her 2:22:56.

Throughout the fall, her training more closely reflected her prep for Berlin in 2019 than her build-up to the Olympic Trials five months later—around 70 to 100 miles a week rather than 100 to 130.

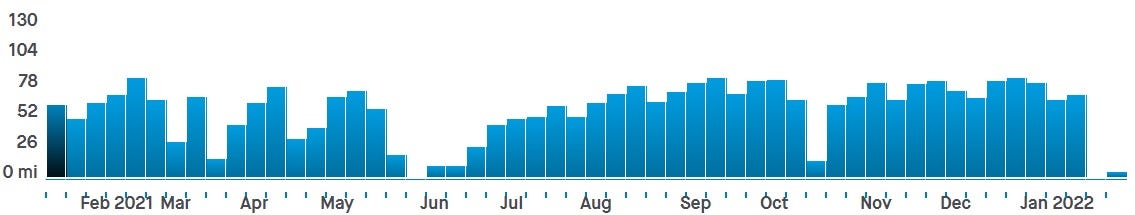

2021 was a strange year for D’Amato in every way. According to a Runner’s World article in October in advance of the Chicago Marathon, D’Amato signed with Nike in February, then spent most of the spring injured. She visited an endocrinologist who, she said, told her she’d die if she continued to run. She skipped the Olympic Trials 10,000 meters as well as the Cherry Blossom 10-Miler in September. The Chicago Marathon did not go nearly as well as the Marathon Project had ten months earlier, with D’Amato running 2:28:22 for fourth place. But given the year she’d had, this wasn’t terrible and scaled accurately with her pre-race comments about her expectations about managing something in the mid-2:20s.

From the article:

Her weekly mileage has been a little lower than in the past—70 to 90, with one full day off a week, compared to 80 to 100 before the Marathon Project (and 100 to 130 afterward, before the injury).

D’Amato’s progression to a 2:22:56 marathoner a little over a year ago was itself the product of modest overall recent volume, considering what it takes to get most women there. Her 2:28:22 in Chicago followed a period of mileage comparable to her Marathon Project training load, but she had been hurt or otherwise off her physical game for much of the year.

The picture only starts to appear truly unusual in the next few months. D’Amato, running the same 65 to 85 miles week she’d done to prepare for Chicago, somehow broke through to 1:07:55 and 2:19:12 fitness. Those two times themselves represent different performance levels—most 1:07:55 half-marathoners would struggle to break 2:22:00 or even 2:23:00.

The real idea here isn’t to fact-check D’Amato’s statements or the media’s ability to report them accurately. It’s to try to see how a 2:19 marathoner could have been assembled from the given elements. Because honestly, there’s no precedent I know of. She basically coasted into setting the American record.

It’s important to emphasize, since all I’m looking at is here training volume and some of you are unfamiliar with my past work, is that I don’t think mileage alone spells marathon success; no one does. The issue is that longtime observers expect a certain bare mileage minimum of anyone running as fast for the marathon as D’Amato just did, and D’Amato hasn’t gotten close to that lately, or really ever. And for someone as fast as she is, there is nothing remarkable about the faster training miles she does run.

“There’s more than one way to the top” may sound cutesy coming from someone who just did something unexpected. But it’s basically a claim that shortcuts to success exist in marathon running, and that recent injuries and modest training mileage won’t keep you from exploding onto the world-class stage at age 37 if you find clever ways around them.

This sort of claim has been made regularly ever since people started racing marathons, and it is simply not supported by pre-2021 evidence. On the other hand, every once in a while, a truly different athlete comes along—at least according to the hopeful narrative that fans of endurance sports always initially cling to, but usually dissolves in scandal within a few months or years.

Regarding the inevitable question of whether D'Amato could have doped her way into the record books—and when a distance runner does something remarkable, people have every reason to be suspicious, especially given the recent travails of another swoosh-wearing American female distance icon—that seems less worth speculating about than ever. I don’t think nearly as many people care if their favorite athletes cheat as was once the case; most who do are graybeards and golden girls watching through binoculars from high in the bleachers, where every “fan” is just mired in the pleasant habit of showing up to watch people play a familiar game, with the teams and even the rules a thrice-removed concern.

Whenever message-board or Twitter speculation about an athlete’s medicine cabinet erupts in the aftermath of an off-the-charts performance by a runner who has never tested positive for a banned substance, two camps immediately form: Those who insist that history is repeating itself, including the excuses and rationalizations they’re seeing from the athlete’s supporters, and those who say it’s always bad form to express such cynicism about an ostensibly clean athlete, with some in this camp even claiming such chatter constitutes libel. The new Wokish wrinkle is some of the “don’t say that” types assigning catastrophic labels like “dangerous” to such talk, even when it doesn’t include direct doping accusations. An entire fragile-yet-despotic class of nominal liberals has emerged, people who think that opinions they don’t like—even ones that have no bearing on their own lives whatsoever—should be winked out of existence rather than confronted on a line-item basis or merely ignored.

But apart from that cancellicious transformation of our communication norms, again, I don’t think that even most of today’s genuine running fans or even half-immersed followers would be as disappointed as their counterparts in eras past to learn that one of their heroes was doping. They want them to avoid the adverse consequences of registering a doping positive, of course, and therefore want them to not get caught. This is mainly because everyone now reporting on running to a wide audience is, thanks almost entirely to social media, far too cozy with every top athlete or someone that athlete knows to report adverse facts about that athlete. Not only do these pundits not want to lose access to, say, an entire club, but they don’t want to feel like they are piling on. And this human tendency has been compounded by a generation of “journalists” being incurious and incompetent by nature; they possess only half of the courage, smarts, and integrity as their predecessors in the field while requiring twice as much. I chalk this up to distance running being a sport that is a joy to take part in and exhilarating to watch your friends and loves ones do, but dismally silly otherwise—an observation no one has ever even tepidly disputed.

It’s also impossible to pretend that the running media is concerned with meaningful ethical standards of any sort. Those media have been fervently trying to topple female sports by calling for their stocking with male bodies and lying all along about the scientific particulars. They have contributed to the proliferation and gleeful promotion of widely embraced course-cutting and otherwise scam-happy “influencers” lending illegitimate support to social-justice causes. They have pushed the idea that certain subpopulations of people by definition can do no wrong, while others, by the same fiat, are always wrong.

If a well-liked American athlete is caught doping this year, a template is already in place for how the media will handle it. The Nike effort last summer to pretend Shelby Houlihan didn’t dope her way into a suspension worked well on the general public, but everyday sports fans being fooled, or not really caring, is standard fare. But the response of the running community itself, people who knew better and pretended not to, was more damning. At root, “Burritogate” was an attempt to make one athlete look less guilty. But in effect it was a trial balloon—will even running journalists and experts swallow our bullshit?

Well, virtually all of them did. So now Nike and anyone else with a pulse knows how easy it will be going forward to just yell “BULLSHIT!” if an American hero or heroine is popped for PEDs. No one in the sport will really believe it, but the level of volume of bullshit will be sufficient to maintain a delusion of American exceptionalism when it comes to cheating. And if the athlete is a person of color, the media will suggest it’s wrong to even subject such beleaguered individuals to doping controls at all.

My own lack of concern about the integrity of professional women’s records and running is related to these things, but distinct from them. The International Olympic Committee decided to outsource the determination of its gender policies to a bevy of Wokish imbeciles, who dutifully came back in November with a bunch of anti-woman, pro-lunacy guidelines. Anyone with a brain recognizes how stupid this is, and World Athletics is free to do as it chooses. But if people who don’t belong in Olympic and World Championship races are allowed to compete in them, then it’s hard to find fault with women at the level of a Francine Niyonsaba who decide to try to level an unfair playing field with drugs. Sure, that’s still a kick to the crotch of other top women, but unfair systems compel rule-breaking by people with a lot at stake.

I won’t review all of the coverage of D’Amato’s record here, but the worst take I saw was, fittingly, by the impressively fluffy Talya Minsberg, the jogging editor at The New York Times. She’s another member of the NYT power-cliche-spouting herd who likes to wow readers with her 20/20 hindsight.

Who were all these naysayers? No love for “High hopes” or Erin Strout? (Come on, “she might even go for the American marathon record” counts for something.) Why didn’t Minsberg write about this stuff before any allegedly improbable events happened? Can’t a woman athlete accomplish anything great without a purposeful villain being inserted into the story?

The line “Together, D’Amato and Hall point to the future of American distance running, one in which runners are not expected to retire at 30” shows that Minsberg knows nothing at all about the sport. But she doesn’t have to—she can write whatever diseased and girlish nonsense she wants, because discerning running fans don’t read what’s printed in the NYT except to malign it with unfettered gusto.

Finally, and to me this is the best part: Whatever happened to just giving up, currently the primary “feminist” message of The New York Times? Shouldn’t go-getters like D’Amato and Sara Hall be considered apostates for not sitting on their asses and moping as part of a take-charge thing? This is all such a laughable invitation to sit around drinking wine and toasting your own iPhone 13 that it’s hard to imagine what runner or would-be runner gains anything from reading this paper’s “sports” columns.

There are few people left who notice any of these erstwhile oddities, and fewer still who care to remark on them when they do. Battered by the never-ending COVID-19 circus, the news-consuming world prefers at this point to engage in a combination of insane fatalism and highly selective and dubious hero worship, and the media is more than eager to keep things spinning along in that reckless direction.

Maybe all of this will seem less important, even to me, if missiles start dotting the skies of Kiev next week. But if that happens, at least we* all still got to see one hell of a marathon run by Keira D’Amato.

(Lack-of-an-editor’s note: My use of “data” as a singular noun in the subtitle is, while acceptable by today’s non-STEM editorial standards, technically wrong; I should have written “those data paint.” But because I have already once again resorted to a trite metaphor, I’m leaving the subtitle as it went out in the e-mail version of this post. [Oh yeah—“email” is also now okay.])