The level of structure your marathon buildup requires is mostly a function of your experience and psychology

Once experienced and proven across relevant distances, all marathoners need just as much training intensity as ever, but some of them need fewer islands of specific positive feedback from the watch

While being coached by Pete Pfitzinger in 2003, I went from favoring two ideas about marathon training to considering them virtually essential to success at the distance. One is the importance of having a weekly (or otherwise non-randomly regular) medium-long run, and the other is the need to rely on multi-week cycles, not weeks, as repeating base periods within a marathon-training block.

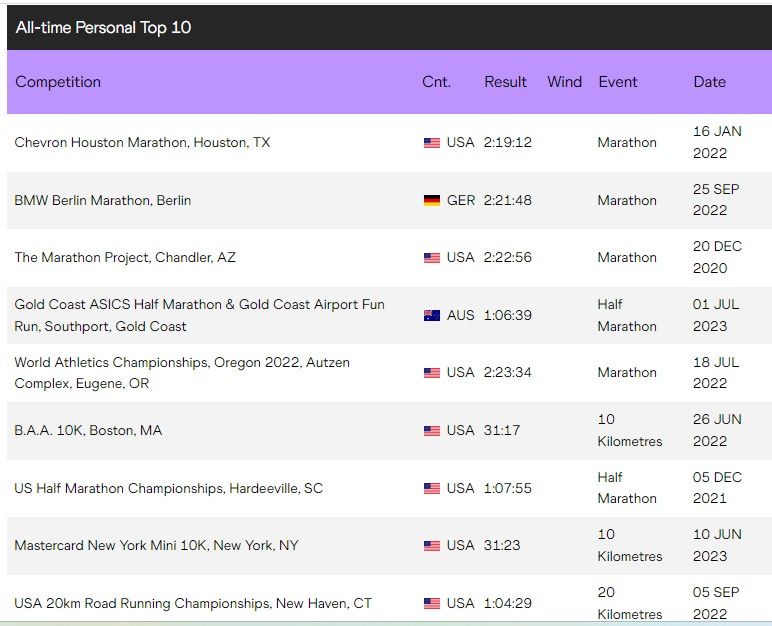

I’ve known elite or otherwise successful marathoners to use two-week repeating blocks, but most seem to believe that fourteen days is not enough time to incorporate every type of required workout. And American half-marathon record-holder and wisecracking mother-of-three Keira D’Amato uses disciplined four-week cycles, although the only discernible pattern within them on a surface-level analysis is varied mileage (something like 65, 75, 85, and 90).

Some successful marathoners don’t rely on strict training schedules at all. They instead determine where they want to be fitness-wise at given points along the way to game day and how they want to assess this. Someone with proven success at the distance1 requires neither the psychological reinforcement of marathon-pace runs that systematically increase in distance at fixed intervals nor their specific physiological rewards. A veteran marathoner can get away with racing half-marathons at just less than all out and calling these “marathon-pace runs” or even “tempo runs” even if neither term strictly apples.

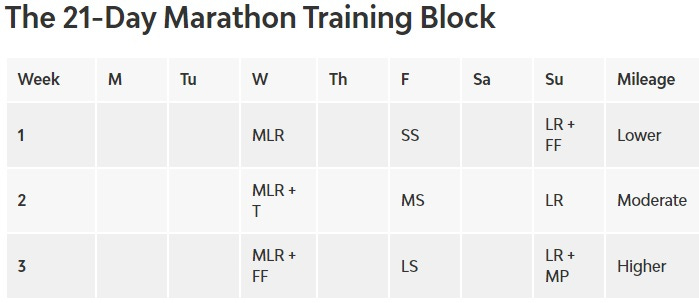

I’ve always preferred three-week cycles for myself and anyone who insists on obtaining advice in the form of a schedule. I’ve gone over this before, both on this site and in various pieces published by corporate outlets, most of the latter having been deleted without explanation in recent years by cowardly editorial figures (owing, I suspect, to my affably rational and nonconformist nature).

I’m bringing this up now because I want to create a bridge between those who enjoy the reliable rigidity of day-to-day schedules and the runners who favor guideposts over formal guidance. An example of someone in the latter category is a hypothetical runner with a 2:50 personal best after six attempts and wishes to run under 2:45 in a marathon four months away. Having bumped up her mileage significantly in the past six months, she is coming off a 1:17:00 half-marathon, a personal best by two and a half minutes.

According to former University of Oregon head track and field coach Robert Johnson, all it takes to be a coach in this sport is an understanding of math. He’s on the right path, as all it takes to figure out approximately how fast you can run a marathon, if you’ve run a few, is your half-marathon time.

A 1:17:00 half-marathon translates to something in the range of 2:42 for most people. But this runner also has the knowledge of being a 1:20:30 half-marathoner when she was a 2:50 marathoner, allowing for considered differences between race courses, weather, and the usual nontrivial minutiae. If she is now three and a half minutes better in the half, she has sound reason to believe she can be more than seven minutes faster over a full marathon, or sub-2:43:00.

This runner can safely organize her training around reliable marathon-buildup elements such as long tempo runs, long runs of any sort, and medium-long runs. She can race relatively frequently over shorter distances if she likes, as she is sanguine enough about the prickly aspects of higher mileage to not fret of these don’t go well (and often, these do go well). If she can run a 20-miler less than all-out at 6:15 pace, non-tapered, three weeks before her marathon, then she can all be but be assured of running her goal time of sub-2:45:00 (which is clearly on the conservative side).

It doesn’t matter precisely how this runner got into shape to do what she’s about to do. Her body doesn’t care how far apart her harder sessions were as long as its muscles got enough rest in between them. She has all the reason there is to be confident, because she doesn’t need as many benchmark certainties during her build-up as others.

The three-week scheme below can actually be reduced into something simpler.

Although the specificity of the workouts means that this is by definition an irreducible cycle, they key days are the same each week, the workouts on those days reduce to MLR (Wednesday), track-style repetitions (Friday) and long runs (Sunday). This is not hard to remember, and the week can be frame-shifted in accordance with personal life schedules (for example, while unconventional, a pattern of Tuesday long runs, Friday medium-long runs, and Sunday track sessions would be just as sound).

Someone following a strict schedule would be certain to do fast-finish-style medium-long runs ten or eleven days before or after fast-finish-style long runs, and would do these fast-finish runs one week after a corresponding run of the same length and type (a tempo run embedded in the MLR and an MP run embedded in the LR). This doesn’t merely satisfy most runners’ mild-to-severe OCD and functional-autist tendencies; it is a legitimate effort to properly balance stresses.

Someone who would rather commit to, say, a certain amount of mileage and a certain number of indicator workouts might be better off working from the basic rotation of (MLR)-(sub-5K-race-pace reps)-(LR) is he or she desires a plan at all, and being certain to run hard enough, often enough, to be boosting fitness.

Then there are runners who may have tried one of these approaches out and found it okay, but somehow lacking, either in lacking focus or not having enough of it. The condensed seven-day pattern is the bridge. The only reason we humans use “weeks” at all is ultimately because of the moon, now known to be a way station for menacing yet queerly incompetent extraterrestrials. But because we do, it’s necessary to make some concessions to this while resisting the temptation to cave to it in ways that belie the realities of adaptive physiology.

Before I die, I will attempt to explain why the medium-long run is so important, despite other Internet visitors having done so repeatedly going all the way back to the days when we first learned the truth about Roswell and anal-probes—and I don’t mean South Park’s critical expose’ of same.

“Success’ in the context of marathon racing means outperforms one’s shorter-distance times at any objective ability level, not necessarily running objectively fast marathon times. A shining example of a superior runner who somehow sucked at the marathon is 2:08:46 guy Zersenay Tadese, whose pre-VaporFly 58:23 half-marathon time should have “easily” landed him in 2:03-2:04 territory.